On the 12th day of the Second Month of the year on the old Japanese calendar corresponding to 1868, the last shōgun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, went into seclusion at Daijiin, a subtemple of Kaneiji, the Tokugawa family temple at Uéno in Edo (modern-day Tokyo), to demonstrate his allegiance to the Imperial government—leaving the task of picking up the pieces of his fallen regime to Katsu Kaishū and Ōkubo Ichiō, two of his most trusted vassals. Two months later, Yoshinobu left Daijiin to return to his native Mito and place himself under house confinement at the Kōdōkan, the official school of the Mito domain. When the last shōgun finally left the capital, it was a “spectacle beyond words,” Kaishū wrote. “Everyone wept.” People lined the roadway, kneeling on the bare ground and facing downward. Around the same time, troops of seven feudal domains entered Edo Castle. Twelve or thirteen samurai from each of them inspected the interior of the castle; the citadel was placed in the custody of the Owari domain, and the troops and weapons were surrendered to Kumamoto. [The above is a slightly edited excerpt from Samurai Revolution, without footnotes.]

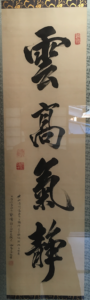

In the Ninth Month of the following year, Yoshinobu was released from house confinement. Around that time he composed the calligraphy shown above, which he sent to Kaishū, as a token of appreciation for his loyalty and service. Today it hangs on a wall in a room of the Kōdōkan.