This year marks the 27th year of the era called Heisei in Japanese chronology. Throughout Japanese history new era names have been promulgated to mark an extraordinary occasion or event, such as the enthronement of an emperor. The present emperor, Akihito, ascended the throne in January 1989, upon the death of his father, Hirohito, posthumously called Showa, the name of the era in which he reigned.

Emperor Showa reigned for over 62 years, the longest in an imperial line spanning 125 generations. At his death at 87, he was the longest-living emperor in Japanese history. His funeral ceremonies, including a somber procession which I witnessed among hundreds of thousands of his bereaved subjects gathered in the streets outside the compound of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, were grand affairs befitting a man who during his lifetime had been worshipped as a god.

The Imperial Palace occupies the grounds of the former castle of fifteen generations of shoguns, including Tokugawa Iéyasu, the founder of the Tokugawa Bakufu, the military regime which ruled Japan for two and a half centuries. The castle was surrendered by the vanquished Bakufu to the new imperial government in the spring of 1868, as a result of peace talks between Katsu Kaishu and Saigo Takamori, leaders of the respective sides. After that the illustrious Emperor Meiji, Showa’s grandfather, occupied the inner-palaces of the castle, including the Main Citadel, which had been the residence of the shoguns, and the West Citadel, previously occupied by the families of the shoguns’ sons. These and most of the original castle structures have been lost to fire, including the gate called Sakurada-mon, renowned as the site of the assassination in 1860 of the shogun’s regent, Ii Naosuké, the most powerful man in Japan.

Sakurada Gate was rebuilt during the reign of Emperor Showa’s father. I have visited the site many times. Standing before the gate, I have tried to conjure up in my mind’s eye the scene on that unseasonably snowy morning in late spring over a century and a half ago, when the regent was cut down by a band of eighteen samurai representing Imperial Loyalism. They killed him for his alleged irreverence to the emperor and treachery in having concluded foreign trade treaties without the emperor’s blessing, and his subsequent harsh treatment of feudal lords, nobles of the Imperial Court, and fellow Imperial Loyalists.

Since the palace is located at the city center, one might best visit Sakurada-mon during the still of an early spring morning – and imagine a soft snow falling:

A sudden pistol shot; bloodcurdling screams of the regent’s bodyguards and assailants; the clanging and banging of the tempered steel of their swords; the dull, thick sound of steel cutting through human flesh, then a beheading, men fleeing with the head, others dying – at the onset of an age of terror and the beginning of the end of the Tokugawa Bakufu.

Standing amid a sea of humanity to catch a glimpse of the emperor’s funeral procession, I found myself wondering if the spirits of Ii Naosuké and the others who had died on that day were not among us, to witness that epochal event on that cold winter morning nearly 129 years after the infamous Incident Outside Sakurada Gate.

For updates about new content, connect with me on Facebook.

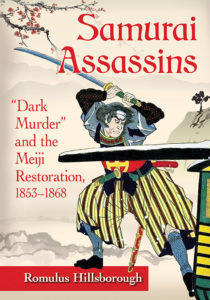

Ii Naosuke’s assassination is the subject of Part I Samurai Assassins.