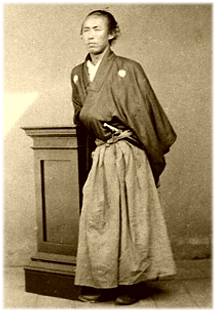

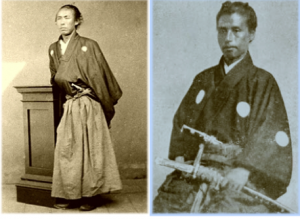

Sakamoto Ryoma & Katsu Kaishu

It is well known that Katsu Kaishu and Sakamoto Ryoma had a very close relationship for a couple of years. But their relationship abruptly ended with the dismissal of Kaishu as the shogun’s commissioner of warships and his subsequent house arrest near the end of 1864, for harboring the likes of Ryoma and other known renegades intent on overthrowing the shogun’s government. And though the two men would never meet again, neither could have accomplished his greatest task without the other.

Kaishu taught Ryoma how to navigate a steamship, state-of-the-art technology that enabled him to establish and operate his merchant marine (Kaientai=Naval Auxiliary Corps), by which he ran guns for the revolution after his break with Kaishu. All of that was essential to Ryoma’s greater achievement of brokering an alliance between Satsuma and Choshu against the shogunate in early 1866. Satsuma was led by Saigo Takamori, to whom Kaishu had introduced Ryoma just before his dismissal from the government – and it is doubtful that without his Kaishu connection Ryoma would have been in the position to even talk to Saigo. Without the Satsuma-Choshu Alliance, of course, it is highly unlikely that the Meiji Restoration would have happened as and when it did – that is to say, it is doubtful that it would have been led by Satsuma and Choshu between the end of 1867 and early 1868.

The shogunate was abolished and the Imperial government was established at the end of the Twelfth Month of the year Keio 3 – January 3, 1868. Saigo represented the Imperial government in the talks with Kaishu to avert all-out civil war in Edo (modern-day Tokyo) in the spring of 1868. Kaishu, as commander of the military forces of the fallen shogun, agreed to surrender the shogun’s castle in Edo to avoid war. But he later remarked that had anyone but Saigo represented the Imperial government, “the talks would have broken down immediately.” Catastrophe would have followed, undoubtedly changing the course of history – and Katsu Kaishu would not have gone down in history as the man who saved the great city of Edo from the ravages of civil war.

[Read Part 2 of this series here.]

For updates about new content, connect with me on Facebook.

For more on Katsu Kaishu’s relationships with Ryoma and Saigo, see Samurai Revolution.