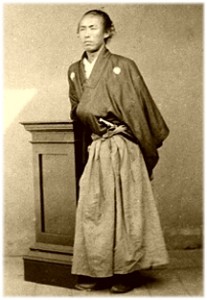

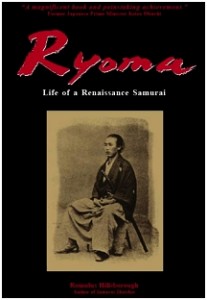

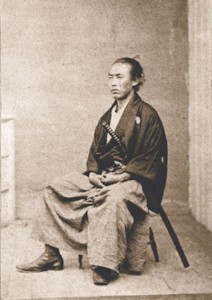

Sakamoto Ryoma & Katsu Kaishu

Sakamoto Ryoma became a political outlaw upon fleeing his native domain of Tosa on a rainy night in the spring of 1862, amid unprecedented social and political upheaval. Following is a slightly edited excerpt from my Samurai Revolution, Chapter 11 (without footnotes):

The crime of fleeing one’s han (i.e., feudal domain) was among the most serious in samurai society. It not only entailed forsaking one’s feudal lord and clan, but also abandoning one’s family—cardinal sins in a society based on Confucian morals. But Ryoma, an extremely independent sort, was unlike most men of his time. He was an iconoclast who would prove to be an enigma to many of his confederates in Tosa and other clans. Few if any of his fellow Imperial Loyalists, for all their avowed loyalty to the Emperor (and indeed readiness to die for their cause), had the audacity to throw off their loyalty to their han. But Ryoma did. In fleeing, it seems, he demonstrated his dissatisfaction with feudalism, including feudal lord and clan, and intended to break the feudal bonds forever.

His dissatisfaction had sprung from a gnawing resentment of the iniquities in feudal society (particularly Tosa), and more recently from his rejection of the violence perpetrated by his fellow Tosa Loyalists. While many of his friends were ready and willing to kill men of the Bakufu (i.e., Tokugawa Shogunate) and their supporters, Ryoma, an original member of the Tosa Loyalist Party, would ultimately turn peacemaker, bristling at unnecessary bloodshed even as he opposed the Bakufu to the bitter end. And while other “patriots of high aspiration” clamored to expel the barbarians and overthrow the Bakufu, they were jealous of the position of one another’s han in a post-Tokugawa Japan. Few, however, had a viable plan for the future. But Ryoma did—based on an uncanny foresight by which he saw beyond the boundaries of the feudal domains toward a unified Japanese nation. And it was another famous outsider, Katsu Kaishu, who would nurture that vision in Ryoma’s very supple mind. [end excerpt]

[Part 1 of this series was posted on Sept. 30, 2015.]

For updates about new content, connect with me on Facebook.

Katsu Kaishu is the “shogun’s last samurai” of my Samurai Revolution, in which I wrote a detailed account of his relationship with Ryoma.