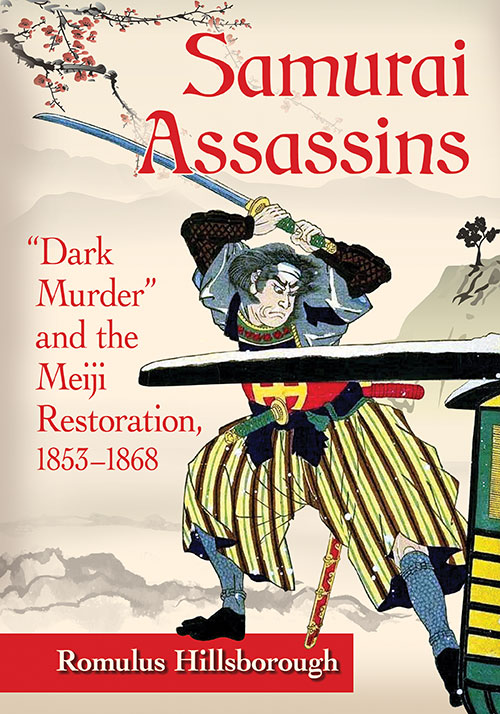

With my forthcoming Samurai Assassins: “Dark Murder” and the Meiji Restoration, 1853 – 1868 expected to be published sometime between spring and summer, 2017, I thought readers would benefit from the following brief synopsis:

The Japanese word for assassination is ansatsu, “dark murder,” and its significance in the samurai-led revolution which was the “dawn of modern Japan”—when the shogun’s military government was abolished and Imperial rule restored—forms the substance of Samurai Assassins.

For all the impact of “dark murder” on the revolution, most of the assassinations covered in Samurai Assassins have thus far received only cursory, if any, attention by Western writers, though the assassins and their deeds are an indelible part of the popular Japanese literary genre that focuses on the final years of the shogun’s government.

The shogun’s government, known as the Tokugawa Bakufu (or simply Bakufu), was controlled by the Tokugawa family, whose head held the title of seiitaishogun—commander in chief of the expeditionary forces against the barbarians (“shogun” for short)—conferred by the Emperor. The shogun ruled the isolated island nation peacefully for two and a half centuries on the Emperor’s behalf from his castle at Edo (modern-day Tokyo) in the east, while the powerless Emperor was sequestered in his palace at Kyoto in the west. But the era of peace ended when the Bakufu could no longer enforce isolationism against the industrial and technological advances of Europe and America. While Hong Kong was ceded to Great Britain in 1842, the specter of Western imperialism reared its ugly head off Japanese shores. When a squadron of warships commanded by Matthew Perry of the United States Navy entered the bay near Edo in the summer of 1853, that specter hit home. The modern era had reached Japan. It was the onset of fifteen years of chaos and turmoil and violence, which would not subside until the collapse of the Bakufu and the restoration of Imperial rule—the series of events collectively called the Meiji Restoration.

During the decade after Perry’s arrival Japan was divided into two schools of thought. “Revere the Emperor and Expel the Barbarians” was embraced by samurai who called themselves “Imperial Loyalists” (“Loyalists,” for short). Meanwhile, the Bakufu and its allies advocated “Open the Country.” The Loyalists rejected the shogun as the legitimate ruler of Japan because he had failed in his most fundamental purpose of keeping the foreigners out, while the Bakufu and its allies believed that expelling the foreigners would be impossible without first modernizing the country militarily and industrially, which required opening up to foreign trade, technology, and ideas.

The Emperor had been a powerless figurehead for centuries until the early 1860s, when Loyalists from samurai clans of western Japan, most notably Satsuma, Choshu, and Tosa, gathered in Kyoto to rally around the Imperial Court. Those samurai colluded with noblemen of the Court to orchestrate a renaissance of Imperial power, while the Bakufu and its allies believed that the reins of government must remain with the tried-and-true military regime at Edo. Restoring rule to the politically inept Court, they said, would jeopardize the sovereignty of the country. The two sides headed toward a final showdown, while the most farsighted among them realized the imperative for the samurai clans to unite as one powerful nation to fend off Western imperialism.

Samurai Assassins will be the only thorough presentation and analysis in English of “dark murder” and the assassins who committed it, without which the Meiji Restoration as we know it could not have happened. On a deeper level, the book is a study of the ideology behind the revolution. My previous book, Samurai Revolution (Tuttle 2014), is a comprehensive history of the Meiji Restoration and the first ten years of Imperial rule. Samurai Assassins provides an in-depth overview of the Meiji Restoration while focusing on significant men and events, and ideology, not expatiated in my previous book. The following breakdown does not include the twenty-two chapters, or the front or back matter:

• Introduction: On “Dark Murder”—and the Existential Crisis and Rediscovered Purpose of the Samurai Class

• Part I: The Assassination of Ii Naosuke and the Beginning of the End of the Tokugawa Bakufu

• Part II: The Rise and Fall of Takechi Hanpeita and the Tosa Loyalist Party

• Part III: The Assassination of Sakamoto Ryoma

• Epilogue: The Second Existential Crisis of the Samurai Class

Samurai Assassins is based mostly on primary sources and definitive secondary sources in Japanese. Among the primary sources are letters from Takechi Hanpeita, the stoic samurai par excellence who is the focus of Part II. Takechi composed the letters in his squalid prison cell, to converse with his wife and sisters, and to communicate with his cohorts on the outside who had been able to avoid arrest. His letters to his cohorts, written in formal language and tone befitting a samurai, provide an insight into his thinking, including his stoic philosophy, which is not seen in any other documents. His letters to his wife and sisters, on the other hand, overflow with the tender feelings of a husband and brother, and include self-effacing humor, complaints, despondency, and melancholy absent in the other letters. To the best of my knowledge, Takechi’s letters have rarely, if ever, been used by non-Japanese writers.

I will report more in this blog on Samurai Assassins as the publication date approaches. Look for updates, including publication date, on Facebook.