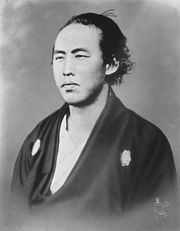

I began studying the life of Sakamoto Ryōma in the mid-1980’s to research my novel Ryoma: Life of a Renaissance Samurai. It was during that time that I discovered the underlying theme of his life: a relentless quest for freedom. Immediately following the scene in which he flees Tosa, I wrote that “abandoning Tosa was Ryoma’s giant leap across the border which had separated him from freedom,” and that he “had chosen to throw himself into a cauldron of political and social chaos” for freedom. “Freedom was what Ryoma had longed for, and it was for freedom that he had sacrificed both country and home. The freedom to act, the freedom to think, the freedom to be: these were the ideals that drove him on the thorny road toward salvation, the salvation of Japan.”

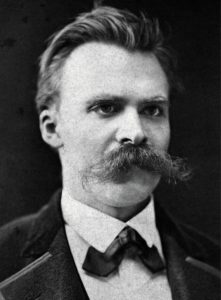

It wasn’t until much later that I delved into the works of Nietzsche, another famous lover of freedom. I discovered that despite their vastly different historical, cultural, and ideological backgrounds, Ryōma and Nietzsche were kindred spirits. I perceived an uncanny resemblance between the provocative German thinker whose ideas resonate throughout the twentieth century and beyond, and the audacious samurai who changed history. Ryōma and Nietzsche were contemporaries, though the latter lived many years longer than the former; and both were modern thinkers. But while Nietzsche was a philosopher, Ryōma was a man of action who lived some of Nietzsche’s fundamental ideas, including the exhortation to “live dangerously.”

“I welcome all signs that a more virile, warlike age is about to begin, which will restore honor to courage above all. For this age shall prepare the way for one yet higher, and it shall give the strength that this higher age will require some day—the age that will carry heroism into the search for knowledge and that will wage wars for the sake of ideas and their consequences. To this end we now need many preparatory courageous human beings. . .” .And so, Nietzsche exhorts courageous human beings who are “seekers of knowledge” to “live dangerously!” [Nietzsche, Friedrich. Walter Kaufmann, trans. The Gay Science, sec. 283. New York: Vintage-Random, 1974. The philosopher R. J. Hollingdale points out that here Nietzsche is not inciting people to arms, as he is often misunderstood to do. His gist, rather, is seen in an earlier line of Nietzsche’s: “Strife is the perpetual food of soul.” (Hollingdale, R. J. Nietzsche: The Man and His Philosophy, p. 144. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1999)]

Ryōma was indeed a seeker of knowledge; and though he was a warrior, he was also a peacemaker. The knowledge he sought included Western military science, and modern business and governmental systems to develop a modern navy, establish Japan’s first modern trading company, and write the blueprint for the modern Meiji government. Commanding a Chōshū warship in 1866, he waged war for the sake of ideas and their consequences against Tokugawa forces at Shimonoseki. In arranging for a military alliance between Satsuma and Chōshū against the Bakufu, and composing a plan for the shōgun’s peaceful abdication and restoration of Imperial rule, even while running guns for the revolution, he proved to be a preparatory courageous human being, even in defiance of his allies, Satsuma and Chōshū, who were determined to crush the Bakufu by military force, and his enemies in the Bakufu who opposed the shōgun’s decision to abdicate.

Ryōma began living dangerously when he rejected Confucian-samurai values and the discriminatory class structure of his native Tosa, fled Tosa, and became an outlaw. In 1865, as he worked to broker the Satsuma-Chōshū Alliance, he wrote a letter to his sister Otomé, in which he dismissed men who stayed behind in Tosa as “truly very stupid” for “spending their days in a place like [Tosa] without any ambition at all.” In the following year, he wrote to Otomé, “Rather than staying home . . . and receiving a stipend of rice, it is much more fun to be working for the nation, if only one is prepared to lay down his life.” Ryōma perceived the Bakufu’s Confucian-based social and political systems as a threat to Japan’s sovereignty in an age of Western imperialism; and resolved to live dangerously, he was determined to overthrow the Bakufu.