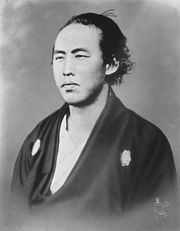

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the assassination of Sakamoto Ryoma, the architect of the relatively peaceful overthrow of the Tokugawa Bakufu. To bolster itself against its formidable enemies – in retrospect a vain attempt to stem the tide of history – the Bakufu established the security force Mimawarigumi, literally “Patrolling Corps,” in the spring of 1864, less than four years before its final collapse. Like the Shinsengumi, its more famous rival within the Tokugawa hierarchy, the Mimawarigumi was established to restore law and order in the Imperial capital of Kyoto. This was just months after the Shinsengumi had distinguished itself in the notorious attack on the rebels at the Ikedaya inn in the Kawaramachi district of Kyoto, just seven short blocks north of the soy purveyor called the Omiya. One of the vice-commanders of the Mimawarigumi was Sasaki Tadasaburo, who around three and a half years later would lead a small group of swordsmen to the Omiya to kill Ryoma.

Ryoma’s assassination remains shrouded in mystery. I focused on Ryoma’s assassins, their motives, and the actual attack in Part III of my new book, Samurai Assassins.