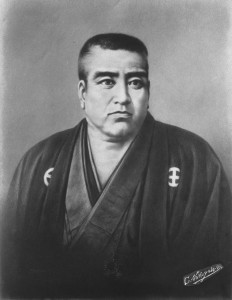

In October 1873, less than six years after the Meiji Restoration, Saigō Takamori, the most powerful driving force behind the “samurai revolution” that toppled the Tokugawa Bakufu to bring about the Restoration, quit the Meiji government, in whose creation he had played the central role. The following excerpt from Samurai Revolution (without footnotes) describes that moment in history:

————————-

Ōkubo [Toshimichi] was the most powerful man in the absolute government. As such he was a dictator—and the dictator was not about to lose the political battle against Saigō. The cabinet convened twice, on October 14 and 15, to decide whether or not to send Saigō to Korea. Ōkubo, having arranged for himself to be appointed to the cabinet two days prior, joined Iwakura [Tomomi] in leading the opposition of just four, including Ōkuma [Shigénobu] and Ōki [Takatō], but supported by Prime Minister Sanjō [Sanétomi]. Backing Saigō were four other councilors: Itagaki [Taisuké], Gotō [Shōjirō], Soéjima [Tanéomi], and Etō [Shinpei]. (Kido [Takayoshi] was absent, claiming illness.) On the fifteenth, Sanjō announced his support in favor of Saigō, but that night again changed his mind. Then on October 19, Sanjō suffered a nervous breakdown. On the next day, by Imperial order Iwakura temporarily replaced Sanjō as prime minister. On October 23 Iwakura pressed the Emperor to oppose a Korea invasion on the grounds that Japan was not yet strong enough to fight a foreign war so soon after the Restoration. The Emperor concurred.

On the same day, just two days before Katsu Kaishū’s dual appointments in the government, Saigō Takamori submitted his resignation from the offices of state councilor, commander of the Imperial Household Guard, and army general. On the next day Soéjima, Etō, Itagaki, and Gotō resigned from the cabinet. Also resigning with Saigō were some three hundred officers in the Imperial Household Guard and the army, all from [Saigō’s native] Satsuma. More than forty officers from Tosa resigned as well. Among the resigning Satsuma officers were Kirino Akihata and Shinohara Kunimoto, both major generals. On October 25 the Emperor summoned Shinohara and twelve other officers of the Imperial Household Guard to the palace to command them to continue serving. The officers ignored the Imperial order. Clearly they were with Saigō. On October 28, Saigō returned to Kagoshima accompanied by Kirino.

[Saigō biographer] Inoue Kiyoshi incisively sums up the outcome of Ōkubo’s political battle against Saigō with the statement: “Ōkubo completely achieved his objective” and buried the call for a Korea invasion, which was nothing less than the political death of Saigō. But Saigō still commanded the hearts and minds of tens of thousands of former samurai throughout Japan who were ready to follow him—even into death.

S