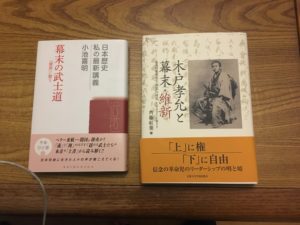

Left: A study of bushido during the Bakumatsu (Bakumatsu no Bushido; Yoshiaki Koike, 2015)

Right: A study of Kido Takayoshi during the Bakumatsu – Restoration period (Kido Takayoshi to Bakumatsu Ishin; Momiji Saito, 2018)

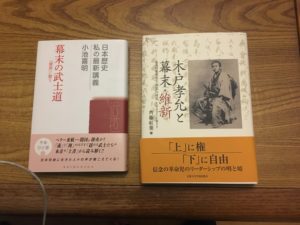

Left: A study of bushido during the Bakumatsu (Bakumatsu no Bushido; Yoshiaki Koike, 2015)

Right: A study of Kido Takayoshi during the Bakumatsu – Restoration period (Kido Takayoshi to Bakumatsu Ishin; Momiji Saito, 2018)

The powerful feudal lords Tokugawa Nariaki of Mito (left) and Shimazu Nariakira of Satsuma (right) fit, to a certain extent, the definition of Platonic “philosopher king.” They were of course contemporaries; and Nariakira supported Nariaki’s son, Yoshinobu, in the political fight against the shogun’s regent, Ii Naosuke, to succeed Shogun Iesada.

Tokugawa Yoshinobu was the last shogun. The most powerful driving force behind the overthrow of Yoshinobu’s government, the Tokugawa Bakufu, and Yoshinobu himself, was Saigo Takamori of Satsuma. Saigo was Nariakira’s favorite vassal (samurai).

I will not discuss the relationship between the two feudal lords here. Nor will I explain why I call them “philosopher kings,” other than to mention that both realized some very important technological, pedagogical and philosophical changes in their respective domains. I have written about both of these feudal lords, and of course about Yoshinobu and Saigo, in my two most recent books, Samurai Revolution and Samurai Assassins.

[The photo of Tokugawa Nariaki is from the Tokugawa Museum. The photo of Shimazu Nariaki is from the National Diet Library.]

Along with Ueno Park, the used bookstore district in Jinbocho is one of my favorite places in Tokyo. I spent hours browsing there earlier this month. I have found so many invaluable books there over the years.

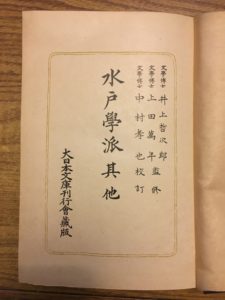

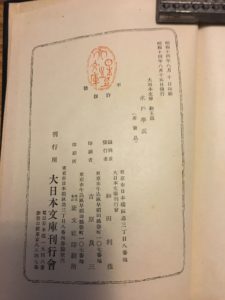

Recently at Jinbocho, I found this gem. Published in 1939, it includes the most important primary sources to focus on the origins of Mitogaku.

The Imperial Chrysanthemum on the front cover is interesting (1939).

[The photo of the Jinbocho street scene is from travel.mynavi.jp.]

Tokugawa Nariaki was the ninth daimyo of Mito and father of the last shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu. He was a reactionary who despised everything Western. He advocated answering foreign demands on Japanese sovereignty with cannon fire and the tempered razor-sharp steel of the Japanese sword. His Mito domain, the cradle of Imperial Loyalism, attracted Imperial Loyalists throughout Japan; and it was Nariaki who coined the Loyalists’ war cry of Sonnō-Jōi—Revere the Emperor and Expel the Barbarians (abbreviated as Son-Jō). (excerpted, in part, from Samurai Revolution, without footnotes)

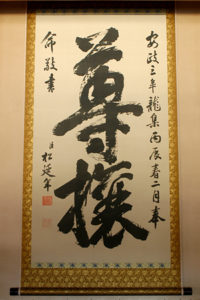

As I wrote in a recent post, in 1841 Nariaki established the famed Kōdōkan within the precincts of Mito Castle, as the official school of Mito Han. The famous “Sonjō” tablet (below) hangs on the back wall of a room beyond an entrance to the Kōdōkan.

[The photograph of Nariaki is from the Tokugawa Museum in Mito.]

This photo of the Tokugawa family was taken in 1889, about twenty-one years after the fall of the Tokugawa Bakufu, at the home of Tokugawa Akitake (4th from the left), the last daimyo of Mito. Akitake’s elder brother, Tokugawa Yoshinobu (at age 52), the last shōgun, is on the far left. The photo, which includes Yoshinobu’s two sons, a daughter, his mother (a princess of the blood of the Arisugawa family) and other members of his extended family, is on display at the Kōdōkan in Mito. Seated next to Yoshinobu is Tokugawa Iesato, the 16th head of the Tokugawa family who succeeded him after he stepped down as shōgun and family head. Around three years after this photo was taken, Katsu Kaishū, the last shōgun’s “last samurai,” adopted a son of Yoshinobu, Kuwashi, as his heir.