Mitogaku: Cornerstone of Imperial Loyalism

In the early part of the nineteenth century an ultra-nationalistic school of thought attained prominence in Mito Han, one of the Three Tokugawa Branch Houses (Go-sanké), whose heads were direct descendants of Tokugawa Iéyasu, the first shōgun of the Tokugawa Bakufu. The school of thought was called Mitogaku. It has been translated as “Mito scholarship”; but from its union of mythology and religion with government and politics, and the fervor by which it was embraced, “Mitoism,” I think, is a better rendering. No matter how it is translated, it was the cornerstone of Imperial Loyalism and the foundation of the revolution which got under way with the assassination of Ii Naosuké in 1860.

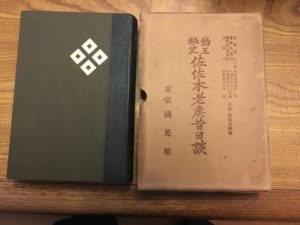

Mitoism had originated much earlier, under Tokugawa Mitsukuni (1628-1700), the second daimyo of Mito who had ruled during the early Tokugawa era. It was taken up in the early nineteenth century by Aizawa Seishisai, a Mito samurai and Confucianist. Both men are associated with two highly influential literary works which have been called the “Old Testament” and “New Testament” of the early Meiji Restoration period. Begun under Mitsukuni was Dai Nihonshi, a history of Japan, which emphasized loyalty to the Emperor. Aizawa, who lived until 1863, four years before the fall of the Bakufu, wrote Shinron (“New Theses”) in 1825. Since ancient times China, the “Central Country,” had been the pinnacle of civilization and culture. But Aizawa affirmed the superiority of Japan and Japanese culture. Shinron, whose teachings of Japanese superiority and Imperial Loyalism would be revived by Imperial Japan’s fascist government in the twentieth century, begins by stating that “our Divine Realm is where the sun emerges. It is the source of the primordial vital force sustaining all life and order. Our Emperors, descendants of the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu, have acceded to the Imperial Throne in each and every generation, a unique fact that will never change. Our Divine Realm rightly constitutes the head and shoulders of the world and controls all nations.”

The spirit of “Imperial Reverence” (Sonnō) did not originate in Mito. Rather, it took root throughout Japan among the educated classes, including samurai, wealthy merchants, landowning peasants, and shōya (peasant officials who oversaw rural villages), under the rule of the Bakufu, based on Confucianism, particularly Neo-Confucianism. But Mito incorporated an intense ultra-nationalism that developed into Imperial Loyalism under the slogan Sonnō-Jōi (abbreviated as Son-Jō)—“Imperial Reverence and Expel the Barbarians”—coined by Tokugawa Nariaki, the ninth daimyo of Mito, and father of the last shōgun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu.

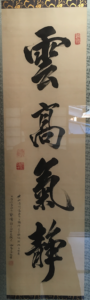

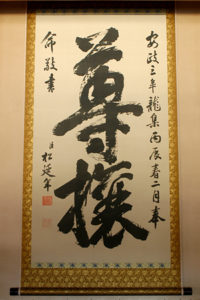

In 1841, Nariaki established the famed Kōdōkan within the precincts of Mito Castle, as the official school of Mito Han. In 1856 he directed the physician Matsunobé Nen, a distinguished calligrapher, to compose the now-famed “Sonjō” tablet, which hangs on the back wall of a room beyond an entrance to the Kōdōkan.

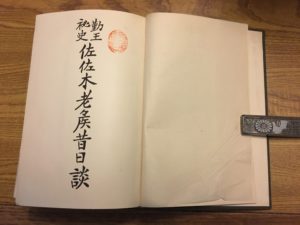

Photos from top to bottom: Sonjō tablet; entrance to Kōdōkan, with Sonjō tablet visible at rear; a volume of Dai Nihonshi

[The text above is a partially edited excerpt (without footnotes) from the Introduction of Samurai Assassins.]