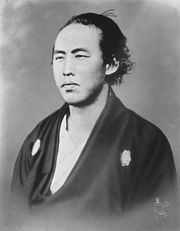

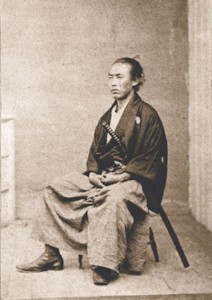

Recently I’ve been discussing Takéchi Hanpeita, while Sakamoto Ryōma has often been a subject of this blog. The two were distant relatives. Ryōma was among the first to seal his name in blood to the manifesto of the revolutionary Tosa Loyalist Party, established and led by Hanpeita. Following is an excerpt from Samurai Assassins:

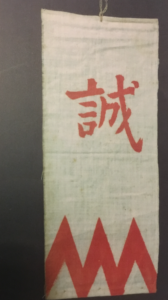

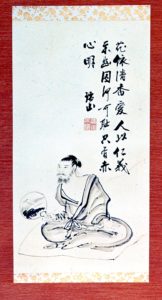

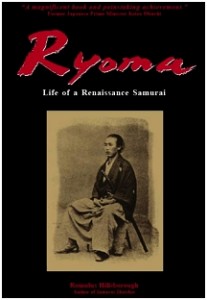

Though Mito Loyalists triggered the revolution with the assassination of Ii Naosuké, as samurai of one of the Three Tokugawa Branch Houses they would never oppose the Bakufu. After the Incident Outside Sakurada-mon, the revolution was led by samurai who felt no allegiance to the Tokugawa. Most of them hailed from han in the west and southwest, ruled by outside lords, most notably Satsuma, Chōshū, and Tosa. Around this time in Tosa emerged two men who would inform the revolution—both charismatic swordsmen originally from the lower rungs of Tosa society. Takéchi Hanpeita, aka Zuizan, was a planner of assassinations and stoic adherent of Imperial Loyalism and bushidō, whose struggle to bring Tosa into the Imperial fold led to his downfall and death. Sakamoto Ryōma, one of the most farsighted thinkers of his time, had the guts to throw off the old and embrace the new as few men ever have—and for his courage, both moral and physical, he was assassinated on the eve of a revolution of his own design. But while Ryōma abandoned Tosa to bring the revolution to the national stage, Takéchi, remaining loyal to his daimyo, was determined to position Tosa as one of the three leaders of the revolution.

[Takéchi Hanpeita is the focus of Part II of Samurai Assassins, while Part III focuses on Ryōma’s assassination.]