With the recent Spanish translation, my Shinsengumi has now been published in six foreign languages, including Japanese.

Japanese (2007), Polish (2007), Romanian (2007), Indonesian (2009), Czech (2011; not included in photo), Spanish (2019)

In 1858 the Tokugawa Bakufu, the shogun’s government, concluded its first trade treaties with Western nations including Great Britain, France, Holland and the United States, igniting the “samurai revolution” that would bring about fall of the Bakufu and the modernization of Japan. The trade treaties were opposed by samurai throughout Japan, led by a few powerful feudal domains, including Choshu [present-day Yamaguchi Prefecture]. In the summer of 1864, Choshu, in violation of the trade treaties, militarily blocked the passage of foreign ships through the strait of Shimonoseki, along the vital trade route at the western tip of the Choshu domain, on the main Japanese island of Honshu. In reaction, England, France, America, and Holland dispatched an allied squadron to bombard Shimonoseki – with the tacit approval of the Bakufu. The bombardment began on the 4th day of the Eighth Month of the Japanese calendrical year corresponding to 1864, with the Choshu forces routed in just four days. Following is a slightly edited excerpt from my Samurai Revolution:

Katsu Kaishu had heard a rumor from Sakamoto Ryoma that Kokura Han, a pro-Bakufu domain located just across the Shimonoseki Strait, had welcomed the allied squadron’s arrival at Shimonoseki, assuring the foreigners that they would not have any trouble from its people. Did the foreign ships attack Shimonoseki at the request of the Bakufu? Kaishu wondered. “Even if Choshu is guilty of crimes,” he noted in his journal, “employing foreign assistance to punish our own countrymen” would itself be criminal. Since “such a crime . . . would be a national disgrace,” the matter must be investigated. [emphasis added; end excerpt]

The president of the United States was recently acquitted for a similar crime by his accomplices in the Senate.

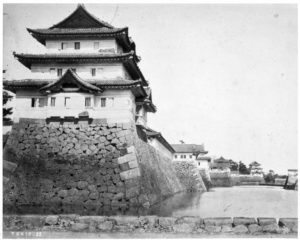

[The photograph of Edo Castle at the end of Tokugawa era appears in Samurai Revolution, p. 488, courtesy of Yokohama Archives of History. Katsu Kaishu is “the shogun’s last samurai” of Samurai Revolution.]

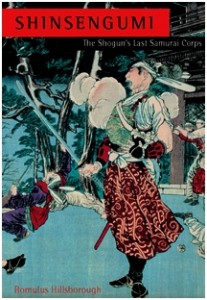

Not to be confused with the Shinsengumi book I’m currently working on, this reprinting is scheduled for release September 2020. (I don’t anticipate finishing the next one for at least a couple more years.)

To go along with the revised title and new cover design, I have written a new Introduction, which features the following information not included in the first printing:

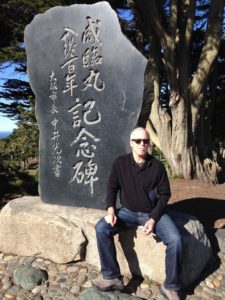

The monument to the Japanese warship Kanrin Maru is at Lincoln Park in San Francisco – a beautiful spot, just behind the Legion of Honor museum of fine arts, overlooking the Golden Gate. The Kanrin sailed through the Golden Gate on St. Patrick’s Day of 1860 – 160 years ago next month – as meticulously recorded by the ship’s captain, Katsu Rintaro (aka Katsu Kaishu), in his journal-like account, published in his history of the Japanese navy, Kaigun Rekishi (海軍歴史).

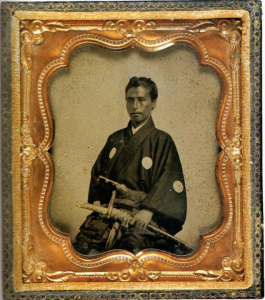

[The famous photo of Katsu Kaishu was taken during his stay in San Francisco. Kaishu is the “shogun’s last samurai” of my Samurai Revolution, a biographical account of his indispensable role in the Meiji Restoration. The photo is used in the book courtesy of Ishiguro Keisho.]

Katsu Kaishu, “the shogun’s last samurai,” was not only an exceedingly interesting man but also one of the highest moral character – an attribute that seems to be sorely lacking among politicians and government officials today. By way of (partial) explanation, I offer the following edited excerpt from my Samurai Revolution:

In early 1868, Katsu Kaishu, as the commander of the forces of the fallen shogun’s regime, was prepared to take drastic measures rather than allow “millions of innocent people to die” in an imminent attack on the shogun’s capital of Edo, modern-day Tokyo, by the army of the new Imperial government. The drastic measures he had in mind were tied to the kenjutsu (Japanese swordsmanship) and Zen training of his youth. “Bushido is found in dying,” asserts the key line of the memorable first chapter of Hagakure, the classic text of samurai values. Death was preferable to disgrace—there was “nothing particularly difficult” about it. Kaishu had reached that critical boundary line to which, it seems, the author of Hagakure had alluded a century and a half earlier. As ever, he wanted nothing more than peace; but, as ever, he would not have peace at any cost. Only a coward would choose life over death without achieving his objective—and Katsu Kaishu, for all his modern sensibilities, was a samurai through and through. Though his objective might be unachievable, he would never accept disgrace—for himself or for the Tokugawa.

[The photo of Katsu Kaishu, taken just before surrender of Edo Castle in spring 1868, is used in Samurai Revolution courtesy of Yokohama Archives of History.]