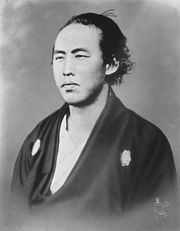

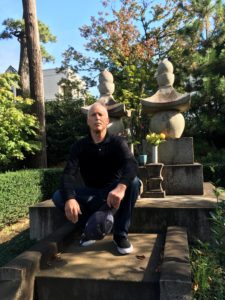

Like many Americans of conscience I am distressed over the current politics and society of our country. And so here are some words of wisdom from Saigō Takamori for these difficult times (slightly edited from Samurai Revolution, without footnotes):

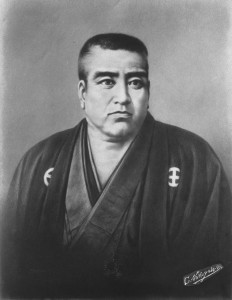

Saigō Takamori, the quintessence of samurai morality, taught that “a great man,” unlike the average man, “never turns away from difficulty or pursues [his own] benefit.” He “takes the blame for mistakes upon himself and gives credit [for meritorious deeds] to others.” He “was physiologically unable to bear” even being suspected of any sort of underhandedness. He had a deep-seated repugnance of “love of self,” which, in his own words, he described as “the primary immorality. It precludes one’s ability to train oneself, perform one’s tasks, correct one’s mistakes,” and “it engenders arrogance and pride.” The ideal samurai “cares naught about his [own] life, nor reputation, nor official rank, nor money,” Saigō taught, even if such a man “is hard to control.”

[The image of Saigo is used in Samurai Revolution, courtesy of Japan’s National Diet Library.]

S