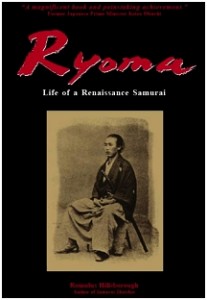

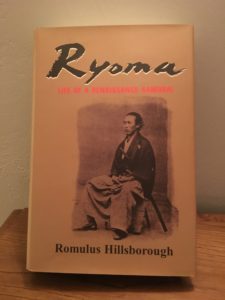

Ryoma fled Tosa Han in the Third Month of Bunkyu 2 (1862). He accomplished all of his important work during the remainder of his life, which was about five year and eight months. He was motivated, in part, by a desire to travel the world – which certainly included the United States. (Ryoma’s mentor, Katsu Kaishu, must have told him about his own experience as captain of the first Japanese ship to reach the United States in early 1862.)

In the introduction to Ryoma, I wrote: “I will never forget my visit to the home of Masao Tanaka, a direct descendent of a boyhood friend of Ryoma’s, located in the mountains northwest of Kochi Castletown. The house was the same one that Ryoma often visited in his youth, and where he apparently stopped, in need of cash, on the outset of a subversive journey he made in 1861 as the envoy of a revolutionary party leader. “My family lent Ryoma money at that time,” the elderly Mr. Tanaka told me, as we stood atop a giant rock behind the house, looking out at the Pacific Ocean far in the distance. Mr. Tanaka informed me that Ryoma liked to sit atop this same rock when he visited the Tanaka family, and where he would indulge in wild talk of one day sailing across the ocean to foreign lands.”

Ryoma of course did not survive the Meiji Restoration to fulfill his dream. But, as explained in part 3 of this series, it took me about five years and eight months to create Ryoma, my purpose of which was to tell his fascinating story to the rest of the world. I like to think that in that sense his dream was partially fulfilled.