Takéchi Hanpeita is the focus of Part II of Samurai Assassins. Following is a slightly edited excerpt, without footnotes:

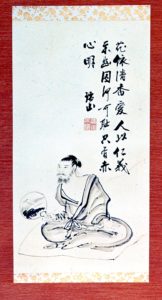

During the summer of 1864, Takéchi painted self-portraits, the bearded face haggard, cheeks hollow, body emaciated after nearly ten months in his squalid jail cell. In one portrait he is seated cross-legged, his chest exposed beneath an open kimono, a fan in his right hand, his left hand placed on his knee. Another depicts a similar pose, with an open book in hand instead of the fan. Pronounced in both is a stoic composure in face of impending doom, founded on an inner-strength developed through years of martial training and study, and manifested through his eyes. Above the image in the first painting he included a poem, beginning with the metaphor of a fragrant flower and rejecting any notion of shame in his imprisonment as long as he lived up to his bushidō-based values. In a letter to his wife and sister probably composed around the same time, he wrote with humor that when drawing his self-portrait he was struck by his own “excessive good looks”—then he suddenly turned serious: “when I look in the mirror [I see that] I am thinner and that my moustache has grown out and my cheeks are hollow.” But, he assured them, they need not worry because “my mind is strong.”

[Takéchi Hanpeita’s self-portrait appears in Samurai Assassins, courtesy of Kochi Prefectural Museum of History.]

For more on Takéchi Hanpeita: