Making progress. But I wonder:

Am I in the middle of writing the next Shinsengumi book?

OR

Is it in the middle of my writing?

Making progress. But I wonder:

Am I in the middle of writing the next Shinsengumi book?

OR

Is it in the middle of my writing?

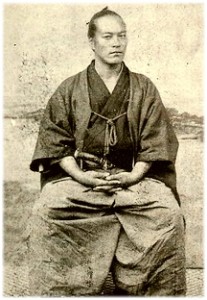

A few years after the Shinsengumi was formed in Kyoto in the spring of 1863, people in Hijikata’s native Hino could hardly believe reports of the bloodletting in Kyoto at the hands of the vice-commander because “he was such a gentle person,” according to one writer. But “Toshizo was a different man with a real sword in hand.” Once when Hijikata briefly returned to Hino, he reportedly told a gathering of family and friends that the blade of one of his swords had “corroded” from overexposure to human blood. [from Shinsengumi: The Shogun’s Last Samurai Corps]

[The photograph of Hijikata Toshizo is in my “Shinsengumi: The Shogun’s Last Samurai Corps,” courtesy of the descendants of Sato Hikogoro and Hino-shi Furusato Hakubutsukan Museum.]

My Inspiration In Writing About the Samurai Revolution (Part II)

Recently I mentioned my inspiration in writing about the Samurai Revolution. The samurai I write about “kick ass,” I said. But I did not say that I am sure that all of them were capable of seppuku– self-disembowelment. This is unthinkable to most people in the 21st century. Following is my rendition of an eyewitness account of the seppuku of Takéchi Hanpeita of Tosa, included in my Samurai Assassins:

Kneeling between his two seconds, Takéchi inspected the blade of the dagger before replacing it on the stand in front of him. Then he removed both arms from his stiff ceremonial robe, baring his shoulders, and loosened the sash around his waist, exposing his lower abdomen. Again he took up the dagger and, wrapping the hilt with the piece of white cloth, plunged in the blade and pulled it across his belly. Blood gushed from the wound as he repeated the process two more times, cutting three horizontal lines as he had vowed. Then deliberately placing the dagger on his right side, he fell forward with both arms extended. That instant the two seconds drew their swords, stabbing him through the heart six times until he was dead. [end excerpt]

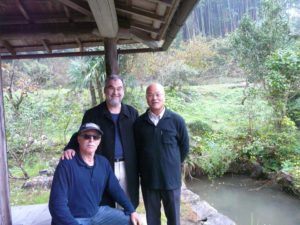

I had the opportunity to visit Takechi’s ancestral home, including his grave, in Kochi in November 2015 (below), with my friends Douglas Stiffler and Mamoru Matsuoka. Professor Stiffler is a great-great grandson of Katsu Kaishu. Mr. Matsuoka, a native of Kochi, is Takéchi’s preeminent biographer. He describes the setting of Takechi’s house as follows (my translation included in Samurai Assassins):

“[in] a quiet mountain hamlet . . . bathed in bright sunshine. Surrounded on three sides by mountains, the south side opens to a small field, and the drawing room is filled with sunlight throughout the day. To the north lies the Kōchi Plain, beyond which is a view of the Shikoku Mountain Range, with the Pacific Ocean spreading out just beyond the hills to the south. The blue sea of these southern climes, which sparkles brightly during ordinary times, can, when the weather turns bad, change to a gray raging billow, enough to frighten even a sailor—and hit Tosa hard.

Tuttle informs me that the publication date is currently set for July 2019: “The [Chinese] publisher ran into some difficulties with the translation which caused the delay.” I think that based on his reverence for China, Katsu Kaishu, “the shogun’s last samurai,” would be glad that it will finally come out.

Often I ask myself: Why do I spend so much of my life writing about men of a culture that is completely foreign to my own, who lived and died in the century before my birth? My answer is always the same: Because these guys are the most inspirational, awesome, and just downright likeable men I have ever “known.” Or in the vernacular, they kick ass! Among them are Katsu Kaishū, the focus of my Samurai Revolution; and Yamaoka Tesshū, Kaishū’s close friend and confidant, renowned swordsman, and Zen adept. Following is an excerpt from Samurai Revolution (without footnotes):

Yamaoka Tesshū died of stomach cancer on July 19 [1888] at age fifty-three. On the day of his death, Kaishū called on him at his home in Tōkyō. Upon entering the house he found the sword master surrounded by visitors and sitting in zazen—the practice of Zen meditation—wearing a “pure white kimono” under a Buddhist robe, “with perfect composure,” Kaishū recalled. He asked his friend if the end was near. “Tesshū opened his eyes slightly and, smiling, replied without [showing] pain, ‘Thanks so much for coming, Sensei. I am about to enter Nirvana.’ Then I said to him, ‘Become Buddha,’ and left.” According to Kaishū’s oral recollection ten years later in October 1898 (Meiji 31), Yamaoka died shortly after he left him. At the time of his death, “he had a white fan in hand.” Chanting a Buddhist prayer, he “smiled at all present, including his wife, children, and relatives,” and, even after he finally died, maintained the proper sitting posture. In manifesting Buddhist enlightenment, Kaishū remarked, Yamaoka demonstrated “just how well he understood bushidō.”

(The photograph of Yamaoka Tesshū is in Samurai Revolution, courtesy of Fukui City History Museum.)