Shinsengumi Commander Kondō Isami rose to prominence after his men assassinated his rival Serizawa Kamo.

This is where I’m at now.

“Think big! Create! Persevere!”

Shinsengumi Commander Kondō Isami rose to prominence after his men assassinated his rival Serizawa Kamo.

This is where I’m at now.

“Think big! Create! Persevere!”

Just beginning Chapter 12 (second chapter of Part 2) of the next Shinsengumi book, exploring Kondo Isami’s political stance.This will be a challenging one. Wish me luck!

“Think big! Create! Persevere!”

This evening my wife mentioned that she saw an NKH program about Ernest Satow’s villa in Nikko. It reminded me of Katsu Kaishū and his relationship with Satow, secretary to Sir Harry Parkes, the British minister to Japan, around the time of the surrender of Edo Castle in 1868. I reminded my wife of the portrait of Kaishū (above), based on the photograph at the British Legation in Yokohama taken by Satow. At that time Kaishū was in command of the forces of the fallen shogun. “I was so very sleepy at the time,” Kaishū recalled years later. “But they dragged me over there. Satow took it, because, as he said, ‘You’re going to be killed.’” Both Satow and Parkes were worried for his life, Kaishū said. And so they urged him to take refuge at the British Legation. Kaishū refused their offer on the grounds that he wouldn’t have been able to perform his job, “if I feared assassination. I thought that dying for the country was the duty of any [patriot] and wasn’t about to do something as cowardly as hide out at a foreign legation.”

Katsu Kaishū is “the shogun’s last samurai” of Samurai Revolution: The Dawn of Modern Japan Seen Through the Eyes of the Shogun’s Last Samurai. I was motivated to write the book based on of my immense admiration for the man – for his moral and physical courage and his humanity.

[The photo of Ernest Satow’s summer villa, on the southern shore of Lake Chuzenji, built in 1896, is from The Japan Times, December 5, 2016.]

The more I know, the more I need to know: That has been my mantra for most of my adult life, including the more than three decades that I’ve been researching and writing about Bakumatsu history (1853 -68)—“the dawn of modern Japan.” Much of my research has included historical texts, journals, letters, and memoirs written by samurai in archaic Japanese. I’ve learned a lot—a real lot—about those crazed, tumultuous, fascinating times. I hope my readers feel my experience and share my fascination.

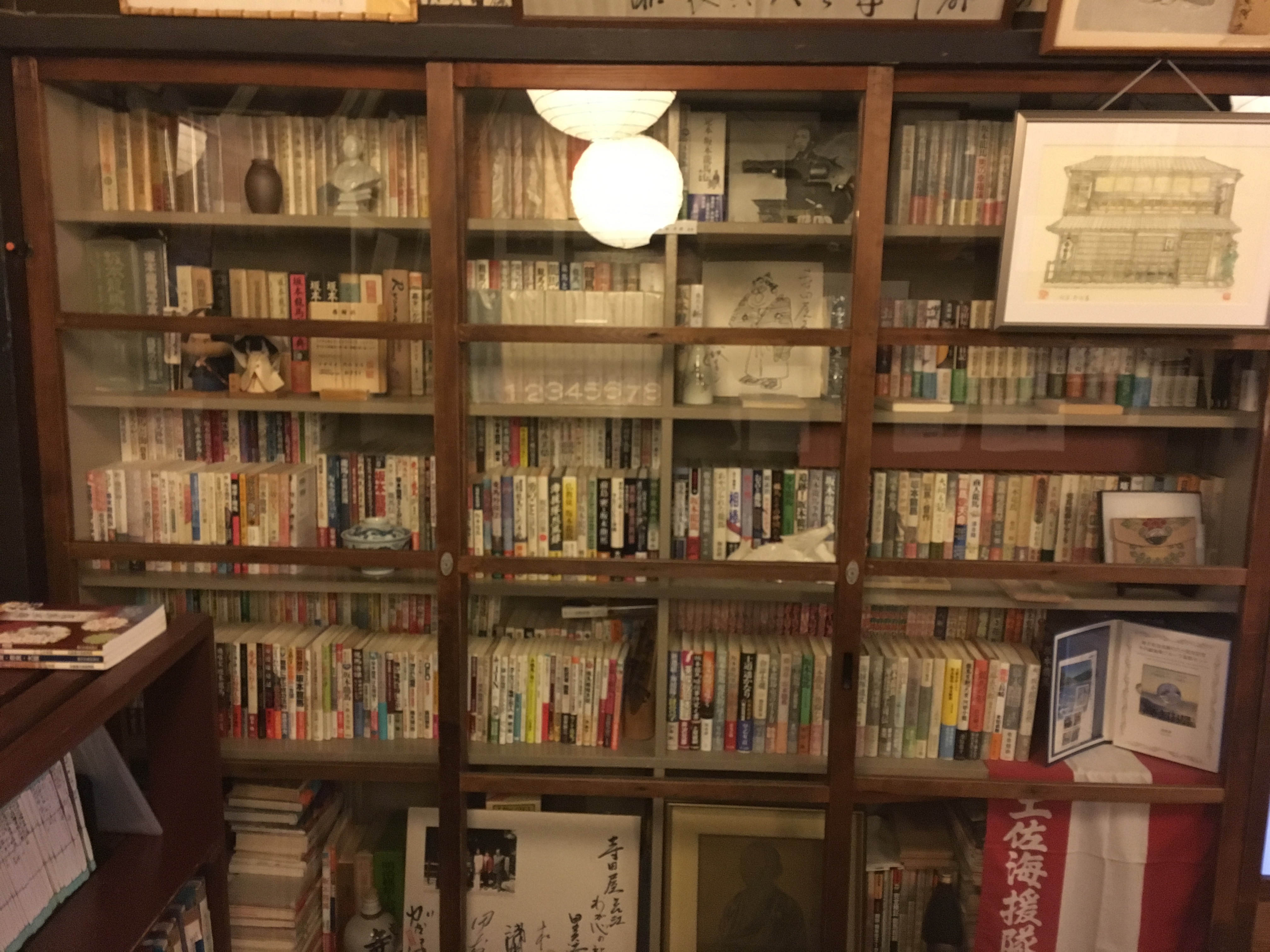

[I took the above photo in the library at the famed Teradaya inn in Fushimi, Kyoto, in October 2016.]

Think big! Create! Persevere!