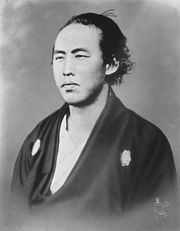

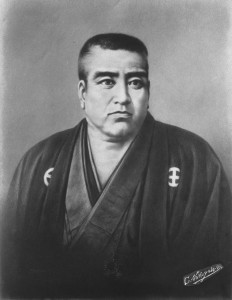

Takéchi Hanpeita and Sakamoto Ryōma both perished during the volatile and bloody years leading up to the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Close friends from the great domain of Tosa, both were “charismatic swordsmen originally from the lower rungs of Tosa society,” I wrote in Samurai Assassins, excerpted below:

Takéchi Hanpeita, aka Zuizan, was a planner of assassinations and stoic adherent of Imperial Loyalism and bushidō, whose struggle to bring Tosa into the Imperial fold led to his downfall and death. Sakamoto Ryōma, one of the most farsighted thinkers of his time, had the guts to throw off the old and embrace the new as few men ever have—and for his courage, both moral and physical, he was assassinated on the eve of a revolution of his own design. But while Ryōma abandoned Tosa to bring the revolution to the national stage, Takéchi, remaining loyal to his daimyo, was determined to position Tosa as one of the three leaders of the revolution. [end excerpt]

Takéchi died by his own hand (seppuku) in the intercalary Fifth Month of the year on the Japanese calendar corresponding to 1866. Ryōma was killed in the Tenth Month of the following year, just before the Restoration. Had they survived the revolution, they very well might have gone on to lead the new Meiji government.