“The Meiji Restoration differs from other great revolutions in that it was brought about by men of the ruling caste—i.e., samurai.”

— from Samurai Revolution, Introduction

It was twenty years ago this month that I began the process of publishing this book. It was a long and tedious ordeal but well worth it, I think. (I hope readers agree.) The book was finally published in February 1999.

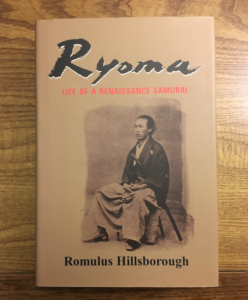

Here is a photo of the original hardcover edition, which is out of print.

The historical novelist Shiba Ryōtarō wrote that the original purpose of the sword was to kill people, though during the centuries of peace under the Tokugawa Bakufu “it became a philosophy.” With the enactment of the Laws for Warrior Households of Kanbun [Kanbun era: 1661-1673], which included a ban on matches using real swords, kenjutsu (“art of the sword”) was treated in some respects as a sport. Starting in the peaceful Genroku era (1688-1704), many samurai, especially those in Edo, led relatively easy lives as administrators rather than warriors – while form and a beautiful technique took precedence over effectiveness in actual fighting, and theory became more important than ability. But with the renaissance of the martial arts during the last years of the Bakufu (1853-68), kenjutsu practitioners shunned form and beauty for practical technique that would work in the real time.

“Ken wa hito nari” (剣は人なり) goes an old saying. The meaning is cryptic but perhaps may be translated as, “The sword is in the man.” It is used to emphasize the importance of “polishing one’s mind” through rigorous training. This concept is articulated by Katsu Kaishū, who learned how to “polish the mind” from kenjutsu training, he said. Then, “… as long as you keep your mind clear, like a polished mirror and still water, no matter what adversity you might encounter, the means for coping with it will naturally come to you.”

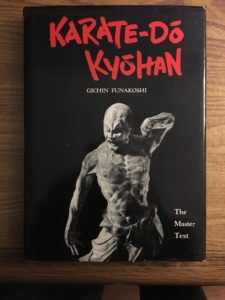

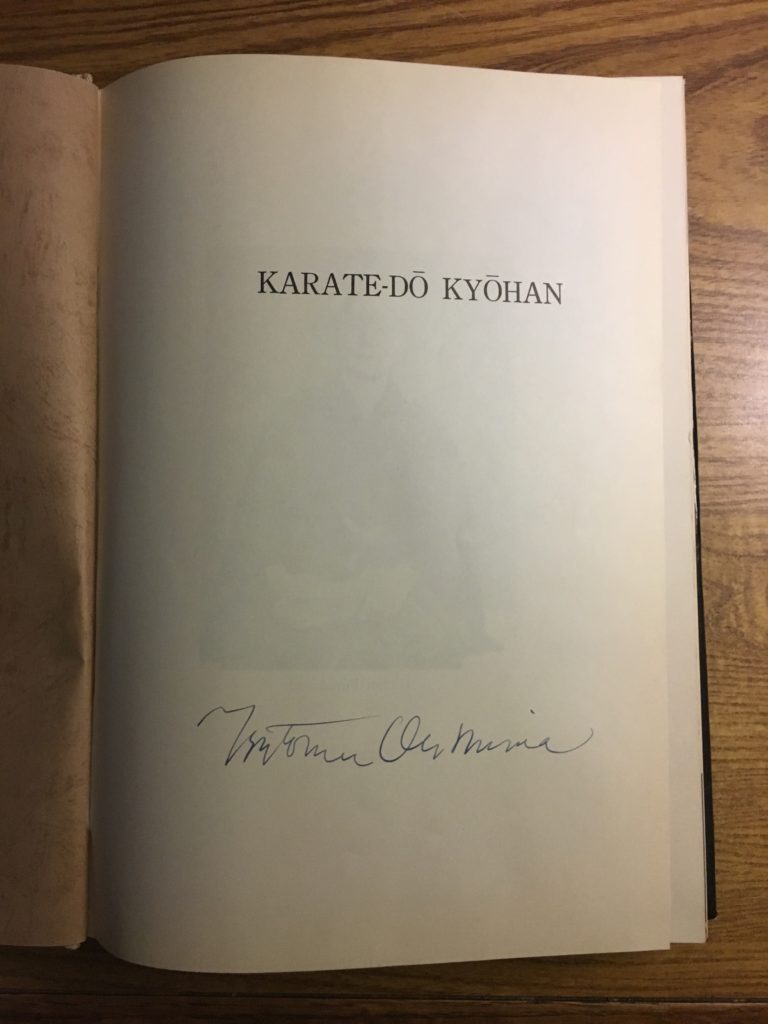

Tsutomu Ohshima’s monumental English translation of the Master Text by Gichin Funakochi was published in 1973. I started practicing under Ohshima-sensei (Shotokan Karate of America) as a kid in Los Angeles in September 1970. I have cherished this signed copy for 45 years.

This new book is a challenge! As I’ve said, the more I know, the more I feel I need to know. Not exactly a formula for a quick or easy completion of this project. My previous book was an introduction to the Shinsengumi. The next one will be an historiography. I like the following definition of historiography offered in Encyclopædia Britannica by Richard T. Vann of Wesleyan University:

“[T]he writing of history, especially the writing of history based on the critical examination of sources, the selection of particular details from the authentic materials in those sources, and the synthesis of those details into a narrative that stands the test of critical examination.”

In the Prologue of my previous book, I wrote that the Shinsengumi was commissioned by the Tokugawa Bakufu to restore law and order amid the gathering revolution. “At once reviled and revered, they were known alternately as rōnin hunters, wolves, murderers, thugs, band of assassins, and eventually the most dreaded security force in Japanese history.”

The Shinsengumi was much more than that.

I won’t finish my next book for at least a couple of years.

Think big! Create!

[The above photo of the original Miniature Shinsengumi Banner appears in my previous book, courtesy of Hijikata Toshizo Museum.]