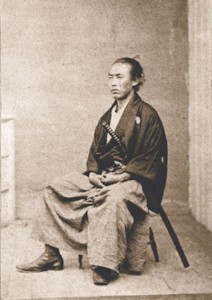

That Sakamoto Ryōma was endowed with an uncanny power of prescience is beyond dispute, as he demonstrated on numerous occasions during the last five years of his life. I have documented these over the years, starting with the biographical novel Ryoma: Life of a Renaissance Samurai (Ridgeback Press 1999), and more recently in Samurai Revolution (Tuttle 2014) and my new book Samurai Assassins (McFarland 2017).

On the 150th anniversary of Ryōma’s assassination let’s consider two striking examples of his apparent foresight of his own death:

• In a letter to his sister, Sakamoto Otomé, about two and a half years before his death, he wrote: “I don’t expect that I’ll be around too long. But I’m not about to die like any average person either. I’ll only die when big changes finally come, when even if I continue to live I’ll no longer be of any use to the country.” (quoted in Samurai Revolution)

• In a letter to a friend written four days before his assassination in Kyōto, he alluded to the great danger facing Japan under the Bakufu and urged his friend to be careful for his life. “Now is the time for us to act. Soon we must decide on our direction, whether it lead to pandemonium or paradise.” (quoted in Samurai Assassins)

S