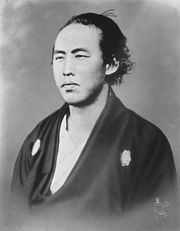

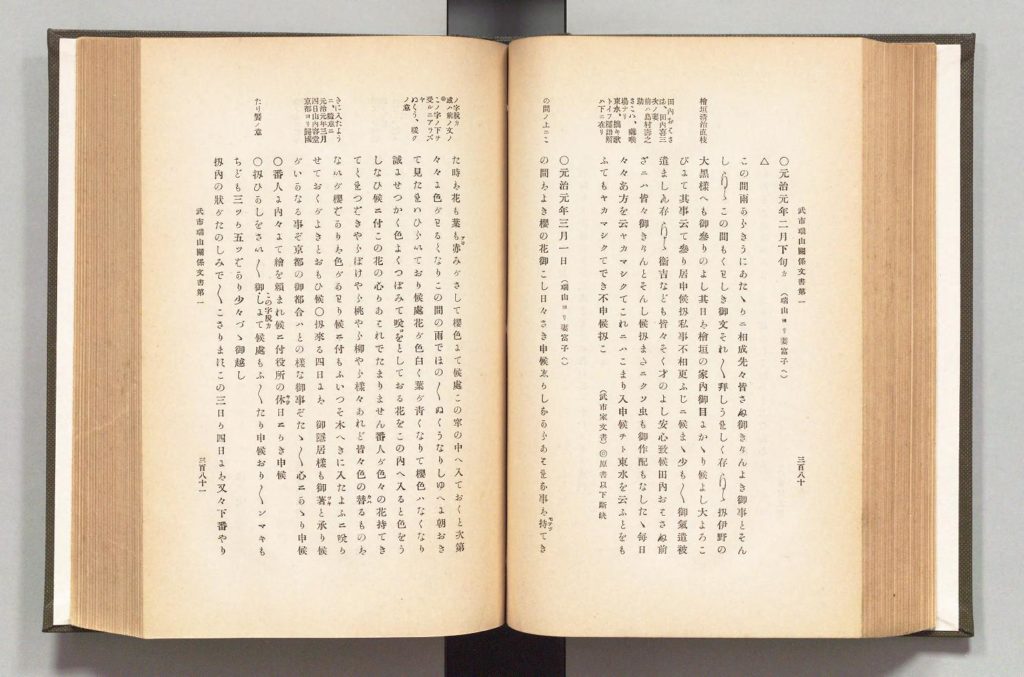

Takéchi Hanpeita, stoic samurai and accomplished swordsman, is the focus of Part II: “The Rise and Fall of Takéchi Hanpeita and the Tosa Loyalist Party” of my new book, Samurai Assassins. After his arrest and imprisonment for seditious activities, he wrote many letters to his wife and sisters, and to his cohorts on the outside who had not been arrested. As I mentioned in a recent post, to the best of my knowledge, Takéchi’s letters have rarely, if ever, been used by Western writers. Perhaps one reason other writers shun his letters is the difficulty of reading them. His letters, particularly those to his wife and sisters, are filled with so-called hentaigana, non-standard and obsolete kana forms, kana being the Japanese syllabary used with kanji (Chinese characters) in the Japanese writing system. Since hentaigana was abolished at the turn of the twentieth century, it cannot be easily read or even deciphered by the untrained eye among Japanese people today.

Nonetheless, as I wrote in Samurai Assassins, Takéchi’s letters to his wife and sisters overflow with the tender feelings of a husband and brother, and include self-effacing humor, complaints, despondency, and melancholy absent in the other letters. As such, they provide a look into the heart of this very important and complex historical figure. An example is the following excerpt from Samurai Assassins:

[A]fter having been locked up for about five months, he wrote to his wife and sister of his commiseration with the “sadness” of the “cherry blossoms that grow pale” in his cell, concluding the letter with the telling words, “I can’t bear that there is nothing I can do”—i.e., that he had no control over his own fate, the fate of Tosa, or the fate of the Imperial Loyalism movement.

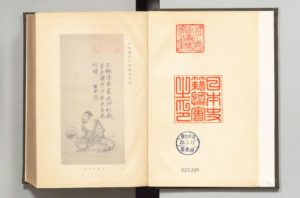

[Takéchi’s letters are published in Takéchi Zuizan Kankei Bunsho (武市瑞山関係文書; “Takéchi Zuizan-related Documents”; Zuizan was Takéchi’s pseudonym). The images of the book shown here are from the from The National Diet Library Digital Collection.]