The double assassination of Sakamoto Ryōma and Nakaoka Shintarō on the eve of the collapse of the Tokugawa Bakufu is an unsolved mystery—but only to a certain extent. What is known of the details of the incident, including the circumstances surrounding Ryōma and Nakaoka just before the attack, their actual murders, and the aftermath, is based primarily on accounts from men representing the two opposing sides in the revolution. On the one hand are accounts from two men who claimed to have committed the assassinations. On the other hand are accounts from the victims’ friends, some of which is based on information heard directly from Nakaoka as he lay dying soon after the attack. Most of these accounts are included in a document entitled “Sakamoto to Nakaoka no Shi” (“The Deaths of Sakamoto and Nakaoka”; 坂本と中岡の死).

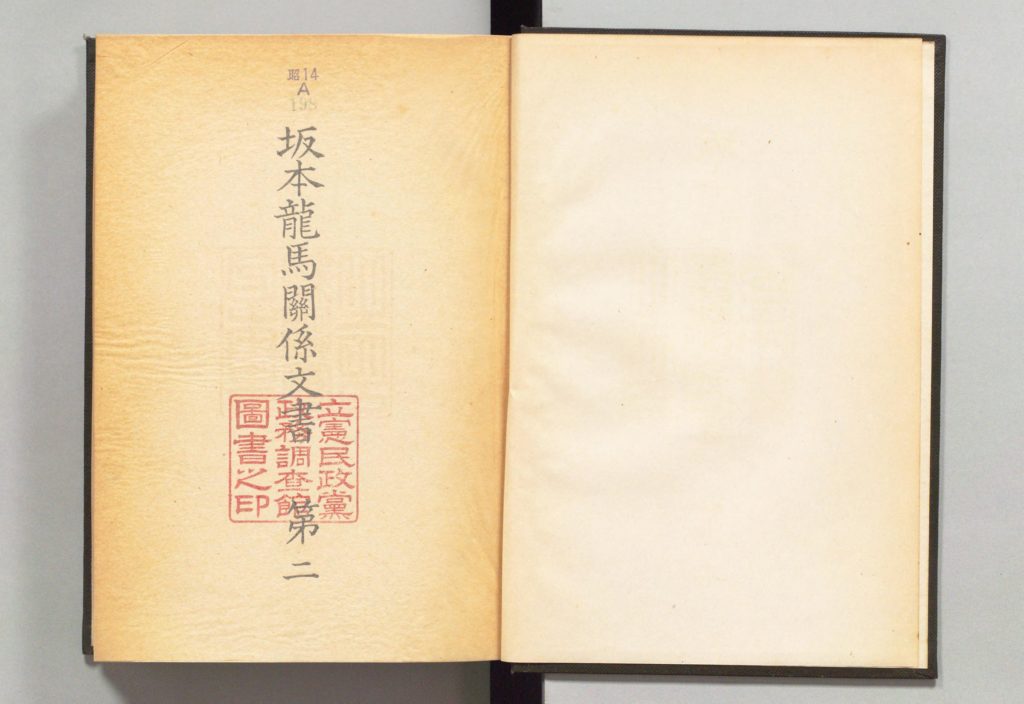

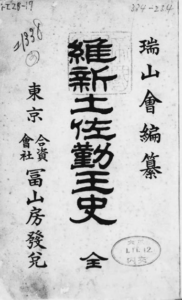

I relied heavily on this document in writing “Part III: The Assassination of Sakamoto Ryōma” of Samurai Assassins. The distinguished Meiji Restoration historian Hirao Michio described it as “indispensible for arriving at a conclusion” as to the facts behind the double assassination of Sakamoto Ryoma and Nakaoka Shintaro, since it “uses every possible piece of historical material in pursuit of the facts.” (「二人の死をめぐってあらゆる史料をあつかい、その真相を追求したもので、この問題史に一断案を下ろしたものとして、見落とすことを許されない労作だ」(平尾道雄氏)) This document was originally published in 1926 as part of the Sakamoto Ryōma Kankei Bunsho, Vol. II (The image of the book shown below is from the from The National Diet Library Digital Collection.).

Matsuura Rei (松浦玲) is one of the most important writers of Bakumatsu-Meiji Restoration history. His work on Katsu Kaishu is particularly important. Kaishu is “the shogun’s last samurai” of my book

Matsuura Rei (松浦玲) is one of the most important writers of Bakumatsu-Meiji Restoration history. His work on Katsu Kaishu is particularly important. Kaishu is “the shogun’s last samurai” of my book