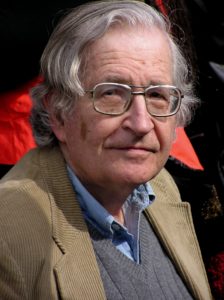

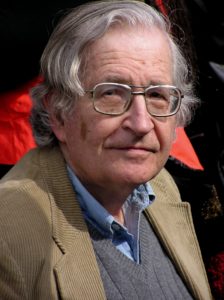

I just caught the last part of an interview with Noam Chomsky, on NHK World. He mentioned the horror he felt when as a teenager in the United States, he heard the news about the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. He also said that he had been appalled by the “reaction” to the news among most people: they went on with whatever they were doing, no matter how trivial, and didn’t really seem to care very much that tens of thousand had just been incinerated, except that it might help end the war. One of the greatest thinkers of our time concluded this interview with the above quote from Antonio Gramsci, paraphrasing: we should be pessimistic about the way things are in this world, but we should be optimistic about perhaps being able to make them better.

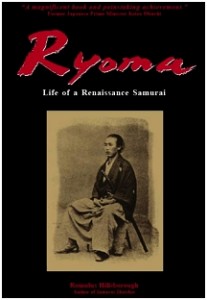

This brings to mind the following quote from another great thinker, Katsu Kaishu, of nineteenth-century Japan, the “shogun’s last samurai” of my book Samurai Revolution: “If the Bakufu [shogun’s government] truly has the best interest of the country at heart, it must willingly fall.” So that the reader may better understand this bold and important pronouncement from a leading Bakufu official, I excerpt the following from Samurai Revolution (from first few pages of Chapter 20):

[begin excerpt] Katsu Kaishū had spent the past year and a half to no avail, he wrote to Yokoi Shōnan on Keiō 2/4/23 (1866). But “I will not be discouraged.” To evade the enmity of the Edo authorities, he would carry on with his “leisurely existence of reading and writing, although it is difficult to forget my anxiety over the fate of the country.” Even as the political and social scene of Japan underwent a sea change of historical proportion, this man of thought and action remained inert, during a seemingly endless intermission backstage—awaiting the cue to reenter.

. . . Kaishū had been informed of “popular unrest” around Ōsaka and Kyōto over rising prices of rice, and as a result, of other commodities. While large quantities of rice were purchased to supply the troops in the impending war, various feudal domains restricted the sale of rice beyond their borders. Unscrupulous merchants cornered the market, driving up rice prices even further. In less than one year rice prices had risen by more than fifty percent. As a result, townspeople in the cities and peasants in rural areas suffered. Early in the Fifth Month rioting broke out at Nishinomiya (about halfway between Kōbé and Ōsaka), soon spreading to Hyōgo (Kōbé) and by mid-month to Ōsaka, where the shōgun was present at his castle. On 5/23, Kaishū wrote of a visit by Sugi Kōji, who informed him that in Hyōgo and Ōsaka mobs attacked and destroyed wealthy merchant houses. Troops fired on the rioters in both cities. Many were killed.

On 5/8 Kaishū noted in his journal that Satsuma “absolutely refused” to fight against Chōshū. On the fourteenth of the previous month, Ōkubo Ichizō had met with Senior Councilor Itakura Katsukiyo at Ōsaka Castle, presenting a letter stating Satsuma’s refusal to send troops. Seizing the high moral ground, Satsuma admonished the Bakufu “not to fight our own countrymen.” It was the shōgun’s duty to preserve the peace in the Imperial Country, not to disturb it. And so to attack Chōshū would be “against the rule of Heaven.” As Kaishū wryly put it at Hikawa, “Itakura was perplexed.”

. . . On the night of 5/27, Kaishū received a letter from Senior Councilor Mizuno, summoning him to Edo Castle on the following morning. “Went up to the castle,” he wrote in his journal on 5/28. Reinstated as commissioner of warships, he was ordered to proceed to Ōsaka immediately. Noting the extraordinary manner in which he had been reinstated, he questioned Mizuno as to the nature of his assignment. “Direct orders from the shōgun,” Mizuno replied. “I had nothing else to say,” Kaishū later wrote. At Hikawa, he recalled that he was “hard pressed for money. So on the next day they gave me three thousand ryō,” about two years’ worth of his salary as warships commissioner. “It was the first time in my life that I got three thousand ryō all at once.”

Before leaving the castle, Kaishū encountered Finance Commissioner Oguri Tadamasu and two others of the French clique. He noted that his political enemies “were surprised” by his sudden comeback. Since he had been out of the loop for a year and a half, they thought that they should fill him in on their secret project—i.e., their scheme to set up a Tokugawa autocracy through French aid. They understood that he was going to Ōsaka, they said. “As you know, the Bakufu is in trouble. It’s going to obtain warships from France. As soon as the ships arrive, we’ll attack Chōshū. Then we’ll hit Satsuma. Once Chōshū and Satsuma are taken care of, there will be no one left in Japan who can challenge us. Then we’ll move forward, subduing all of the other feudal lords. We’ll reduce their landholdings and set up a prefectural system.” Certainly their colleague . . ., they assumed, would agree with their plan. They could not have been more mistaken! “Realizing that it would be a waste of time to argue with them,” Kaishū later wrote, “I kept quiet and listened.”

. . . On the next day, 6/22, Kaishū reported to Senior Councilor Itakura at the castle. This time he held no punches, even pounding his fist as he spoke. “What they have decided in Edo is very wrong,” he told Itakura. If Japan intends to take its place among the nations of the world, it must set up a prefectural system—i.e., feudalism must be abolished and a unified national government established. But, Kaishū admonished, the Tokugawa must not take away the lands of the feudal lords and rule the nation autocratically, claiming to do so for the welfare of the country. “If the Bakufu truly has the best interest of the country at heart,” he said, “it must willingly fall.” [end excerpt]

In other words, Katsu Kaishu was pessimistic about the government which he loyally served, but optimistic about the way his country might be. As we approach the presidential election in the United States, the above ideas of Gramsci and Kaishu are particularly relevant — and I fear for our country. Whichever of the two candidates wins, we will be stuck with perhaps the worst president in our history. So the optimistic question is: how can we fix things?

Read more about Katsu Kaishu in Samurai Revolution, the only full-length biography of the great man in English.