Q: What did Sakamoto Ryoma have in common with George Armstrong Custer and “Wild Bill” Hickock?

A: Like Ryoma, both of the Americans owned a Smith & Wesson No. 2 Army revolver, according to the website of the NRA National Firearms Museum. “Wild Bill” Hickock was carrying one when he was killed in a poker game in Deadwood, Dakota Territory, the NRA Museum reports. Maybe Ryoma was a better shot than Wild Bill.

Smith & Wesson No. 2 Army revolver, same model carried by Sakamoto Ryoma

Shortly after overseeing the conclusion of the Satsuma-Choshu Alliance in early 1866, which would lead the overthrow of the shogun’s government less than two years later, Ryoma was attacked and nearly killed at the Teradaya Inn in Fushimi, just outside of Kyoto. He used his Smith & Wesson to defend himself, as he described in a letter to his family. I quoted the letter in Samurai Revolution, excerpted, in part, below:

Just then the woman I’ve told you about (her name is Ryō, and now she’s my wife), came running up to us from the kitchen and warned, “Look out! The enemy has suddenly attacked. Men with spears are coming up the stairs.” I jumped up and, meaning to put on my hakama [trousers], realized that I had left it in the next room. So I put on my swords, grabbed my six-shooter, and crouched down toward the back [of the room]. My companion Miyoshi Shinzō put on his hakama and swords—and with spear in hand, he also crouched down.

The next minute a man opened the screen a crack and looked inside. Seeing our swords he demanded, “Who’s there?” As he started to come in and saw that we were ready for him, he backed off. Soon there was a racket in the next room. I told Ryō to remove the sliding doors that opened to the next room and the room behind us—and saw a line of ten men armed with spears. . . . We glared at each other for while. . . .

One of us [presumably spear expert Miyoshi] stood holding his spear at mid-level, ready to fight. Thinking that the enemy was going to attack from the [left] side, I shifted my position to face left. Then I cocked my pistol and I fired a shot at [the man] on the far right of the line of ten enemy spearmen. But he moved back, so I shot at another one, but he also moved back. . . .

Now I shot at another man, but didn’t know if I hit him. One of the enemy came in from the shadow of the screen—and with a short sword he cut the base of my right thumb, split open the knuckle of my left thumb, and hacked my left index finger to the knuckle bone. These were only slight wounds—and I pointed my gun at him. But he quickly took cover in the shadow of the screen. Another of the enemy came at me, so I shot another round—but didn’t know if I hit him either. Though my pistol held six bullets, since I’d only loaded five I only had one shot left. I thought I ought to save it for later—and the battle died down a bit. Then a man in a black hood . . . advanced along the wall, standing with his spear at the ready. Seeing him, I cocked my pistol again. Miyoshi was standing there with his spear; I used his left shoulder as a gun mount—and taking aim at the man’s chest, I fired. It looked as though I’d hit him. He lay on his belly crawling forward, as if about to die.

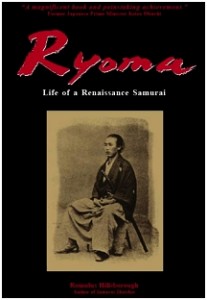

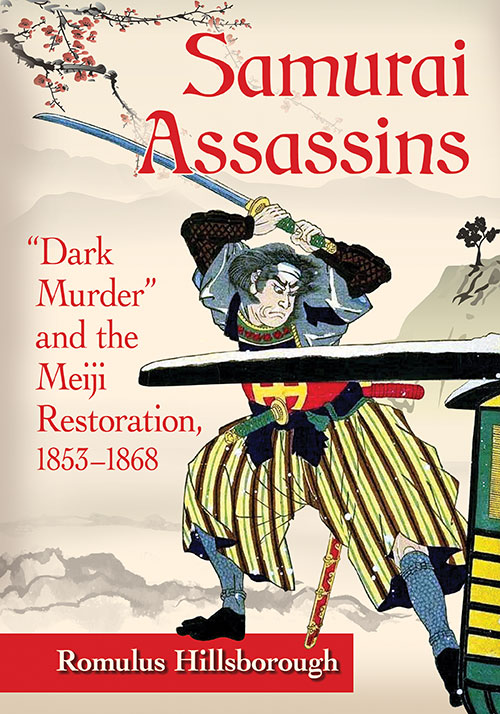

Read the rest of Ryoma’s account of his narrow escape and more about his indispensible role in the Meiji Restoration in Samurai Revolution and in Ryoma: Life of a Renaissance Samurai.