“A hero is fond of the sensual pleasures,” goes an old Japanese saying. It has been suggested that Katsu Kaishu had numerous “concubines” precisely because he was a hero.[1] About such things, Kaishu had the following to say:

“Most of the mistakes a man makes in his youth come from sexual desire. . . . But try as he might, sexual desire is not something that a young man can easily suppress. On the other hand, the most vigorous [driving force] in a young man is the ambition to achieve greatness. It is extremely admirable if he can use the fire of his ambition to burn up his sexual desire. It is a true hero who can calm himself when his passion is aroused. Before he knows it, he will be driven by his ambition to achieve great things . . . no longer thinking of anything else.”[2]

Katsu Kaishu was certainly ambitious. And it is unarguable that he achieved greatness and that he was a hero. But it seems questionable that he ever burned up his sexual desire. He had multiple mistresses even into his old age. Nonetheless, he seems to have respected his wife, Tami. According to one writer, he once said, “Had Tami been born a man, she would have certainly made a fine politician. It is much to her credit that she never quarreled with any of the women I bedded.”[3]

Some of those women were live-in maids at the Katsu residence, including Masuda Ito, the master’s favorite. Ito was “graceful and attentive to detail,” Katsube Mitake reports in his biography.[4] Kaishu had two children with Ito. One died very young; the other one, Itsuko, grew up in the same house as Tami’s children.

Tami’s outward acceptance of her husband’s penchant for other women was probably not indicative of her true feelings, which are perhaps better demonstrated by her reported last words: “Don’t bury me next to Katsu. I want to be next to Koroku,”[5] their son who had died thirteen years earlier in 1892.[6] Tami’s request was not honored. She and Kaishu were buried side by side near Senzokuiké pond in Tōkyō.

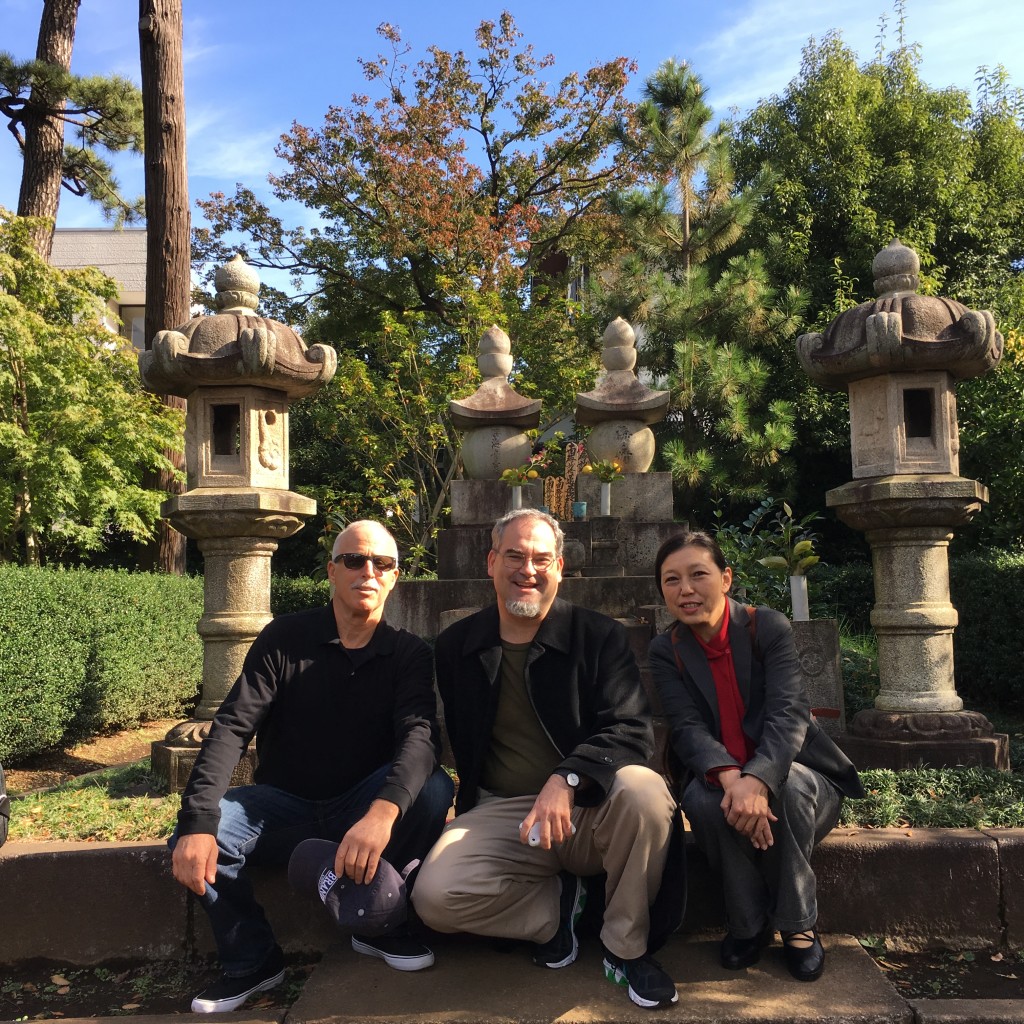

[The photo was taken at the gravesite of Katsu Kaishu and his wife Tami in November 2015. With me are two of Kaishu’s descendants: Professor Douglas Stiffler and Ms. Minako Kohyama. Prof. Stiffler is the great-great grandson of Kaishu and his “Nagasaki mistress,” Kaji Kuma. Ms. Kohyama is the great-great granddaughter of Kaishu and Masuda Ito.]

[1] Katsube Mitake. Katsu Kaishū. Vol 1 (Tokyo: PHP, 1992), p. 44.

[2]Hikawa Seiwa (Katsu Kaishū Zenshū 21; Tokyo: Kōdansha, 1973), p. 295.

[3] Hiyane Kaoru, “Katsu Kaishū wo Meguru Onnatachi,” in Konishi Shiro, ed., Katsu Kaishū no Subeté (Tōkyō: Shinjinbutsu Ōraisha, 1985), p. 155.

[4] Katsube. Katsu Kaishū. Vol 1, p. 434

[5] Katsube, Katsu Kaishū, Vol. 2, p. 438.

[6] Tami died in Meiji 38 (1905), six years after Kaishū. (Takahashi Norihiko, “Henkakuki wo Ikita Josei 75-nin,” in Bakumatsu Ishin wo Ikita 13-Nin no Onnatachi (Bessatsu Rekishidokuhon, October 20, 1979; Tokyo: Shinjinbutsu Ōraisha), p. 290)

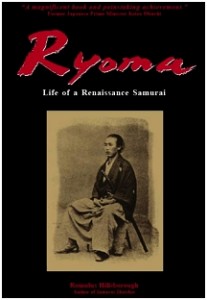

Read more about Katsu Kaishu, “the shogun’s last samurai,” in my book Samurai Revolution, the only full-length biography of the great man in English.