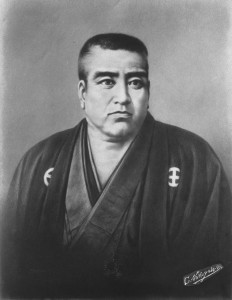

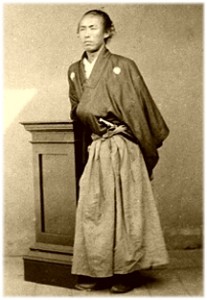

The Japanese warship Kanrin Maru, under Captain Katsu Rintaro (aka Katsu Kaishu), landed in San Francisco on March 17, 1860 (St. Patrick’s Day), as the first Japanese ship to reach North America. On March 23 a local San Francisco newspaper reported: “A few of the Japanese are riding about town to-day, looking in at the shops. At Keith’s apothecary establishment they tarried long”—perhaps because on the previous day one of the crew had died of illness. Kaishu’s detailed description of the Marine Hospital in the city, where “eight of our sailors stayed,” denotes his profound interest in modern American medicine.

The eight Japanese sailors were treated for illnesses they had contracted amid harsh conditions at sea. Kaishu wrote that they shared one large south-facing sunny room, where they were well taken care of by the nurses. Three of them, Gennosuke, Tomizo, and Minekichi, from the seafaring province of Sanuki on Shikoku, died at the hospital. They were young men, in their mid-twenties. Kaishu and US Navy Lieutenant John M. Brooke, who with ten other US Navy sailors had accompanied the Japanese on their transpacific voyage, went to the marble yard on Pine Street to order gravestones, and inscribe epitaphs in Japanese and English, respectively, including “the name of our ship, the names of the deceased, and the dates of their deaths,” for the burials that took place in the grounds of the Marine Hospital.

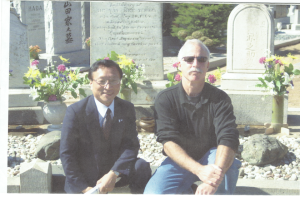

The three graves are still intact, relocated to a cemetery in Colma, just south of San Francisco. The other five ill sailors were nursed back to health, and in August, several months after the Kanrin Maru would set sail on her return journey, made it back to Japan via a ship bound for Hakodate in the far north of Japan.

(In the above photo at the gravesite I am with my good friend Kiyoharu Omino, a distinguished writer of Meiji Restoration history.)

Read about Katsu Kaishu, “the shogun’s last samurai” and his San Francisco experience, in my book Samurai Revolution.