Takechi Hanpeita, leader of the Tosa Loyalist Party whose objective was overthrowing the Tokugawa Bakufu (Shogunate) and restoring Imperial rule, was ordered by the Tosa authorities to commit seppuku on the evening of the 11th day of the intercalary Fifth Month of the Japanese year corresponding to 1865, after languishing in prison for nearly twenty-two months. He had been sentenced to die by his own hand based on trumped up charges of political crimes. But he took solace in the fact that he was at least given the honor of dying as a samurai, rather than be beheaded as a common criminal. The following account of Takechi’s seppuku, cited from my Samurai Tales (originally published as Samurai Sketches), is based on the memoirs of Tosa Loyalist Igarashi Bunkichi. Igarashi based his account on the eyewitness oral account of Shimamura Jutaro, younger brother of Takechi’s wife, and one of two “seconds” who assisted in the seppuku. (Besides being an expert swordsman, Takechi was also an accomplished poet and artist. Zuizan, as he is referred to in the following passage, was his pseudonym.)

At dusk he was brought to the nearby courthouse garden, where he had been interrogated in the past. The scene this evening, however, was different from that which he had known. The ground was specially covered with sand to absorb Zuizan’s blood. Several men in formal dress were seated in a semicircle, facing an area on the north side of the garden furnished with two tatami mats. Two candles burning in two tall stands cast a dim pallor over the grim scene, and Zuizan recognized among the witnesses the two chief interrogators. Suppressing a sudden desire to throw himself upon them, he calmly seated himself upon the tatami.

Set directly in front of him was an untreated, pale wooden stand, on top of which had been placed a piece of clean white cotton cloth and a dagger in a plain wooden sheath. Earlier in the day he had chosen his two seconds, both former kenjutsu students and adept swordsmen, who now sat at either side of him. One of them was the younger brother of his wife, the other Zuizan’s nephew. One of the chief interrogators now read in a loud clear voice the death sentence, after which Master Zuizan bowed deeply. “Thank you for your troubles,” he said to his seconds, taking the dagger in his hand and drawing the blade.

Master Zuizan would now perform his seppuku with meticulous precision. He believed that there were only three proper ways to cut — one straight horizontal line, two intersecting lines, or three horizontal lines. He chose the latter, which was the least common, because it was the most difficult to perform properly. But so weak was his physical condition after one and a half years in jail, that it had been a struggle for him to even walk to the courthouse garden. Over these past several days he had continuously suffered from chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, and a palsy that numbed his entire body. He worried that he would not have the physical strength to slice through the resilient abdominal tissue three separate times. He feared that if he should fail to perform his seppuku beautifully his name would be slandered in death, and his enemies would laugh and call him a coward who was unable to die like a samurai. He had therefore informed one of his guards of the cutting method he had chosen, making him swear to publicize his noble intent in the case that his physical strength should fail him.

“Don’t cut me until I give the command,” he told his seconds. He stared hard at the blade, and then gently replaced the dagger on the stand. He cast a steely gaze at the several witnesses, who, in spite of their exalted positions, were daunted by the superior strength radiating from the eyes of the man with the emaciated body. Master Zuizan now removed both arms from his kimono, baring his pale shoulders, then loosened the sash around his waist, exposing his lower abdomen. He tightened his mind as he summoned all of his mental power into his hands, again took up the bare dagger, wrapped the hilt with the piece of white cloth, and plunged the blade into the left side of his abdomen. Blood gushed from the wound, but without uttering a sound he sliced across to the right side, pulled out the blade for an instant, and plunged it in again, repeating the process in the opposite direction. With the third slice, he released a guttural wail, his only means to summon a final burst of strength. But his seppuku was not complete until he deliberately placed the bloody dagger at his right side, and fell forward with both hands extended directly in front of him. The next instant the seconds drew their long swords, piercing the heart of their beloved sword master. Takechi Zuizan was dead at age thirty-six; and so nobly did he perform his seppuku, displaying his inner purity, that his enemies were left speechless. [end excerpt]

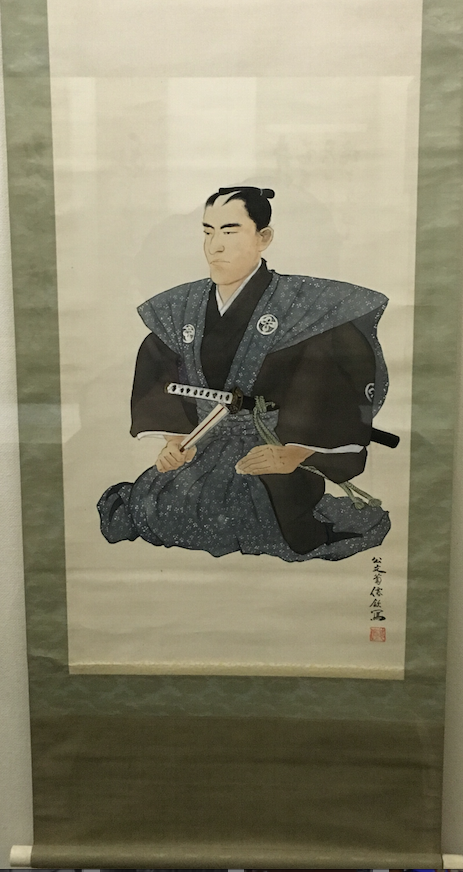

[The monument, located at the edge of a bustling shopping district of Kochi, formerly the castle town of the Tosa daimyo, marks the spot where Takechi Hanpeita committed seppuku 150 years ago. The portrait of Takechi is on exhibit at the Sakamoto Ryoma Memorial Museum in Kochi.]

For updates about new content, connect with me on Facebook.

Samurai Tales is an updated edition of Samurai Sketches. Samurai Tales contains a Forward to the New Edition, and three vignettes at the end of the book which were not published in Samurai Sketches.