As a young boy Katsu Kaishu spent a lot of time at the inner-palace of Edo Castle, which was the residence of the shogun, his immediate family, and the women who surrounded the shogun. He was invited there as a playmate to the grandson of Shogun Tokugawa Ienari. Katsube Mitake, a Kaishu biographer, surmises that he “gained much by spending so much time at the inner-palace during his early youth,” which was “an opportunity that nobody else had,” particularly a poor boy of his low social standing. It was a period in history, writes Katsube, in which “Edo culture had ripened to the height of decadence. By that time Utamaro [Kitagawa Utamaro, woodblock print artist, 1754-1806] was already dead, but Hiroshige [Ando Hiroshige, woodblock print artist, 1797-1858] and Hokusai [Katsushika Hokusai, woodblock print artist, 1760-1849] were both still actively producing. It was a time of refined and delicate lifestyle in the great city of Edo, with its population of more than one million. Edo Castle was a place where the highest standard of that culture was practiced, and where one might imagine that advanced aristocratic tastes, comparable to those of the Palace of Versailles in France, were realized.” (Katsube, Mitake. Katsu Kaishu, vol 1. Tokyo: PHP, 1992: p. 337)

Men were not permitted in the inner-palace, where Kaishu surely learned about human nature, the shogun and his family, who, Katsube imagines, were “coming and going before his very eyes.” The experience would prove to be invaluable to Katsu Kaishu in his future capacity as a high-ranking Tokugawa official. As I wrote in Samurai Revolution, he probably heard the wives in the inner-palace talk about the shogun’s councilors and the feudal lords, and observed the complex relations among the women, some of whom wielded significant influence in the government. “I was a favorite among many of the old women,” Kaishu recalled. “That was a great help to me later in life. When those old women heard that even Saigo feared me, they thought that I had become quite a man.” That he became “quite a man” was in large part because of his father, Katsu Kokichi.

Kokichi, an accomplished swordsman, was not about to let his only son spend too much time with women, but rather took great care that he would be trained in the martial arts. One of Kokichi’s teachers was an extraordinary old man whom he praised as “an exceptional martial artist and superb scholar.” The teacher’s name was Hirayama Kozo (1759-1828). He hailed from an old family of ninja who had practiced their secret art in the service of the shogunate six generations past. He was a highly skilled swordsman who was also trained in the arts of yarijutsu (“spear techniques”), jujutsu and artillery, and was an expert in the tried-and-true Naganuma school of military strategy. Hirayama lived by a daily routine of rigorous martial training and study. According to Kokichi, the old man slept in armor on a dirt floor, as if “always on the field of battle.” He wore only light cotton clothes, even in the dead of winter. He was an ascetic, whose house in Edo Kokichi likened to a “hermit’s dwelling.” Although Kokichi never received a formal education, for about ten years, from age sixteen, he received a classical education in military history through numerous and lengthy discussions at Hirayama’s home.

While Kaishu was still a young boy, his father enrolled him at the fencing school of Odani Seiichiro, a son of Kokichi’s eldest brother. When Kaishu was sixteen, a particularly skilled swordsman named Shimada Toranosuke enrolled at Odani’s school. Soon Shimada, who had come from Nakatsu Han, in the province of Buzen on Kyushu, opened his own school in Edo, which Kaishu joined at age eighteen, “thanks to the efforts of my father,” he recalled. Shimada, who urged his students to practice Zen “to gain a deeper understanding of kenjutsu,” had a profound influence on Katsu Kaishu, who stated that “Zen and kenjutsu became the foundation of my future life.”

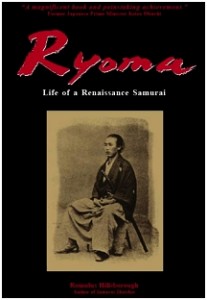

This image of Shimada Toranosuke is taken from the website of Nakatsu City.

For updates about new content, connect with me on Facebook.

For more on Katsu Kaishu’s martial arts training see Samurai Revolution, the only biography of the man in English.