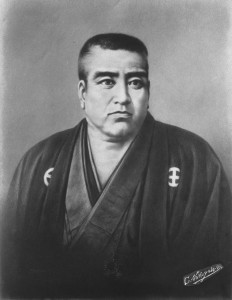

In early 1860 the Tokugawa Bakufu (i.e., the Japanese government) dispatched a delegation of seventy-seven samurai to Washington to ratify a trade treaty with the United States concluded in Japan in the summer of 1858. The Japanese delegation sailed aboard an American naval ship, the Powhatan, while the Bakufu sent the warship Kanrin Maru to San Francisco, as an auxiliary vessel to the delegation. The Kanrin arrived in San Francisco on March 17, as the first Japanese vessel to reach the United States. The captain, Katsu Kaishu, is the “shogun’s last samurai” in my book Samurai Revolution. I gave a whole chapter to the stay of the Japanese in San Francisco, which was closely covered by the local press. Upon landing at Vallejo Street Wharf, the press reported, the officers of the Kanrin, including its captain, took carriages to the International Hotel. The following is from Samurai Revolution (pp. 119, without footnotes):

International Hotel, from “The Annals of San Francisco,” by Frank Soule, et al, originally published in 1854

The International Hotel stood on the corner of Jackson and Kearney Streets in the center of the city. When the samurai alighted in front of the lobby, their strange appearance attracted crowds of spectators, who must have watched their every move. “One wore a light blue gown and trowsers the colors of the sky at sunset, spangled, starred and barred with gold and crimson,” reported the Daily Evening Bulletin on March 20. Each man displayed on his jacket his family crest in white “circular, oval or square patches,” which were “of an import quite unknown to us.” And each wore his long and short swords in the polished scabbards at his left hip, “almost horizontally.” One of them “carried a fan [in his right hand], in his left a walking cane. . . . Almost every man wore sandals generally of grass.” [end excerpt]

As the local people admired the grand spectacle of the samurai entourage, the samurai entourage admired the International Hotel, the likes of which they had never before seen. It was “a beautiful redbrick building four stories high,” Kaishu noted in his journal. Passing through the lobby, they ascended the staircase to a spacious parlor, furnished with “a huge glass mirror, chairs and a harp. The floor was covered by a thick woolen carpet of a floral pattern.” They must have been mesmerized by the sumptuous and spacious parlor illuminated by an enormous gaslight chandelier. Picture them traversing the luxurious carpet to seat themselves awkwardly upon the couches and chairs upholstered with fine woven fabric, and sipping French champagne, as their hosts spoke to them in a language they could not understand. And what would they have thought of the likely spectacle of mustachioed and bearded men sporting Victorian frockcoats, ruffled shirts, neckties, top hats and long black boots, and smoking fat cigars, as they promenaded hand in hand with hoop-skirted ladies? Certainly the samurai would have found it odd that American gentlemen were unarmed and tipped their hats in an uncomely gesture as they passed by.

To be sure, both the Americans and the Japanese experienced culture shock. Kaishu, for example, noted his astonishment that “a man accompanied by his wife [in town] will always hold her hand as he walks. Or he will let his wife walk before him, remaining behind her.” (I wish I could have seen him watching this.)

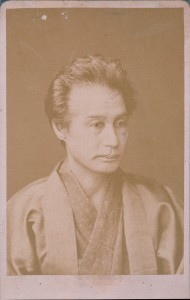

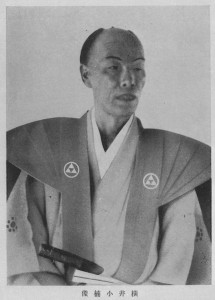

Nonetheless, unlike most of their countrymen, the ship’s captain, along with the official interpreter, Nakahama Manjiro (aka John Manjiro), who had been educated in the United States, had previous experience with foreign cultures. Years later Kaishu commented that during his training at the Bakufu’s naval academy in Nagasaki in the late 1850s, “I met everyone who came [there] from foreign countries”—including ship captains “with whom I spoke candidly about anything and everything.” That Kaishū had (at Nagasaki and through his extensive reading of foreign books) familiarized himself with Western dress and furnishings, and even cigars and champagne (though he rarely drank alcohol), while certain others at the naval academy had not, denotes the flexibility of his very open mind. That he did not blindly follow standards of dress but rather wore his thick black hair tied in a loose topknot, so that, as the Bulletin reported on March 23, “he looked as if he knew nothing of pomatum and gloried in its frizzled, shaggy look,” reveals his outsider’s nature. That he seemed, in the Bulletin’s words, to be “acquainted with the [English] language, and to appearances every inch a gentleman,” bespeaks his self-possession, because Captain Katsu, like the rest of his company except Manjiro, did not understand English.

For updates about new content, connect with me on Facebook.

Read more about the San Francisco experience of Katsu Kaishu in Samurai Revolution, the only biography of the man in English.