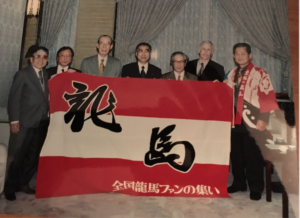

It was 20 years ago this month, December 3, 1999, that a group of us visited Prime Minister Keizo Obuchi at his official residence in Tokyo. Mr. Obuchi was a famous admirer of Sakamoto Ryoma. Our group included five distinguished Japanese gentlemen, all with a unique relationship to Sakamoto Ryoma: Saichiro Miyaji and Kiyoharu Omino, both eminent Ryoma biographers; Dr. Kanetoshi Tamura, then-chairman of the Tokyo Ryoma Society; Kunitake Hashimoto, the “godfather” of Ryoma societies around Japan; and Yasuhiko Shingu, a descendent of Shingu Umanosuke, an original member of Ryoma’s famed Kaientai (Naval Auxiliary Corps), precursor to Mitsubishi.

During the meeting I asked the prime minister to speak about Ryoma and hand out copies of my recently published book at the Group of Eight Summit, which he was scheduled to host in Okinawa the following summer. When the prime minister graciously agreed, I thought that Ryoma was on his way to international stardom. A few months later Mr. Obuchi suffered a stroke from which he never recovered.