[How I wish I could have been present during their first meeting. Here is a slightly edited excerpt (without footnotes) from Samurai Revolution: Chapter 11 (The Commissioner and the Outlaw).]

Ryōma first visited Katsu Kaishū some time between the Tenth and Twelfth Months [of Bunkyū 2, Japanese year corresponding to 1862), though the date is unclear. In light of Ryōma’s Loyalist background and his antiforeign leanings, and the fact that he was outwardly anti-Bakufu, it is not unreasonable to assume that he might have visited Kaishū’s home with blood in his eyes. “Sakamoto Ryōma came to kill me,” Kaishū would say in a newspaper interview years later, on April 3, 1896. But Kaishū tended, on occasion, to exaggerate and embellish upon his past exploits—and, I contend, that tendency was at work during that particular newspaper interview. In fact, it is hard to believe that Ryōma intended to kill him. Ryōma, who hated bloodshed, is believed to have killed only once, and that in self-defense a few years later. Furthermore, with his naval aspirations, Ryōma stood to benefit through amicable relations with the man he would soon call “the greatest . . . in Japan.”

According to Kaishū, Ryōma was accompanied by Chiba Jūtarō on his first visit to Hikawa [Kaishū’s home]. Kaishū must have been forewarned by Shungaku. And it seems unlikely that the adept in Zen and kenjutsuwould have been taken off guard by the two younger and less experienced men. At any rate, Kaishū invited his visitors inside. Ryōma and Chiba would have had their two swords at their left hip. Ryōma, who according to a childhood friend “was of average height,” was much taller than Kaishū, who was only about five feet tall. And, of course, Kaishū would have been unarmed at home. “If you don’t like what I have to say, you should kill me,” he claimed to have told them. The two visitors, probably startled, followed Kaishū into the house. No doubt they were impressed by Kaishū’s pluck, although his tongue was certainly stuck in his cheek! According to Hirao, when the two swordsmen started to remove their swords as protocol demanded, Kaishū stopped them, perhaps to keep the upper hand. “It would be careless of you as samurai to take off your swords in these troubled times,” he reportedly said. Ryōma and Chiba were presently seated in the drawing room. “So, you’ve come to cut me down. Don’t try to hide it. I can see it in your eyes.”

Needless to say, Ryōma did not kill Kaishū. Instead, he listened closely as Kaishū discoursed on the state of the country and the world at large. Kaishū spoke of the futility of trying to defend against the foreign onslaught without a navy, for which Japan needed Western technology. He said that the navy must be a national effort, and not merely a force of the Tokugawa Bakufu. It must include capable young men from all the feudal domains, regardless of lineage, and not only the privileged sons of Tokugawa vassals. Such radical talk from the shōgun’s vice warship commissioner must have stunned the outlaw, who was captivated. Years later Kaishū wrote, “It was around midnight. After I had spoken incessantly about the reasons why we must have a [national] navy, [Ryōma], as if having understood, told me this: ‘I was resolved to kill you this evening, depending on what you had to say. But having heard you out, I am ashamed of myself.’” (It’s hard to believe that Ryōma actually spoke those words, and even if he did, that he meant them. But based on the fact that they were written down by Kaishū rather than reported in an interview, it is also hard to discount them. My only explanation is that Ryōma perhaps said those words to demonstrate to the Bakufu official, and even more importantly to his friend Chiba Jūtarō, his dedication to Imperial Loyalism.) “He told me that he wanted to become my student,” Kaishū wrote. Kaishū thought Ryōma to be “quite a man,” who “had a cool head, and a certain power about him that was hard to penetrate. He was a good man.” He readily accepted Ryōma’s request.

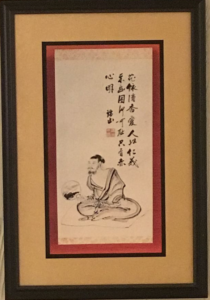

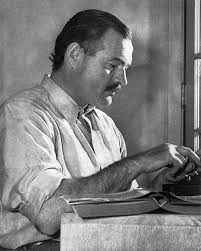

[The photo of Katsu Kaishu, taken just before surrender of Edo Castle in spring 1868, is used in Samurai Revolution courtesy of Yokohama Archives of History. (Katsu Kaishu is the “shogun’s last samurai” of Samurai Revolution.) The photo of Sakamoto Ryōma, taken at Nagasaki in 1866, is used in the book courtesy of Kochi Prefectural Museum of History.]