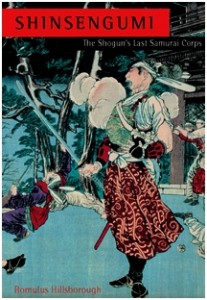

[Following is a partially edited excerpt (without sources cited) from the first few pages of Chapter 8 (“A Brief Discussion on Bushido.”) of Samurai Revolution.]

Bushido, the way of the warrior, is a compelling subject in the study of samurai culture, and much has been written about its moral philosophy. Interpretations of its origins and even purpose vary, at times contradicting or even negating one another. For as Nitobe Inazo writes in his classic English-language treatise, bushido “[i]s not a written code,” but rather “consists of a few maxims handed down from mouth to mouth or coming from the pen of some well-known warrior or savant.” It is “a law written on the fleshly tablets of the heart . . . founded not on the creation of one brain, however able, or on the life of a single personage, however renowned.” Rather, bushido, its tenets seldom uttered, “was an organic growth of decades and centuries of military career.”

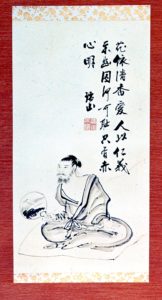

A samurai’s education during the Edo period (1603-1867) was based on Neo-Confucianism, which flourished under the Tokugawa Bakufu (the shogun’s government). It was intertwined with bushido, which, in turn, was inseparable from the way of the sword and the Buddhist teachings of Zen. Of the latter, Nitobe emphasizes its “sense of calm trust in Fate, a quiet submission to the inevitable, that stoic composure in sight of danger or calamity, that disdain of life and friendliness with death.” The samurai class, “a rough breed who made fighting their vocation,” is as old as the institution of feudalism in Japan, dating back to the twelfth century.

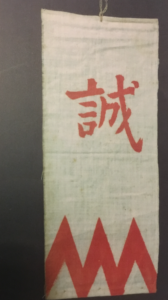

Bushido, however, is much younger, dating back only as far as the mid-Edo period, during the era of Genroku (1688-1704), a turning point in cultural history about a century after the founding of the Bakufu, when many of the warrior class lived relatively easy lives compared to their predecessors. Kaionji Chogoro, in his biographical treatment of Saigo Takamori, writes that the term bushido did not exist until then. During the peaceful Edo period many samurai became administrators—which is not to say, however, that they forgot the arts of war. As professional warriors who received stipends from their feudal lords, they were expected to answer the call to arms at any time. There is an old saying: “Ken wa hito nari” (“the sword is in the man”); and it was also said that there was no such thing as a samurai without a sword. Even as the samurai took up the pen, they were required to wear the two swords; and many of them practiced the martial arts—with the sword, with the spear, and on horseback.

Until the advent of bushido, writes Kaionji, the most important qualities in a samurai had been bravery, honor, and a strong masculine spirit, based on a set of values sometimes called “the way of the man.” Bravery naturally meant bravery in battle, begot of honor and strength of spirit. “The way of the man” worked just fine during the Age of Civil Wars preceding the Edo period, when a man’s worth was measured by his valor on the field of battle. However, since “the way of the man” lacked a strong underlying moral code, it came to be frowned upon as barbaric, and even immoral, during the peaceful, orderly, and more refined Edo period. The samurai required a new set of morals to replace the old. And so bushido derived as a combination of Confucianism and “the way of the man”—without the barbarism of the latter—and might be best defined as “the way of the gentleman.”

The eight virtues of Confucianism—benevolence, justice, loyalty, filial piety, decorum, wisdom, trust, and respect for elders—were incorporated into bushido. Most, if not all, of these qualities were also valued in “the way of the man,” but were not the measure of the man in the older system. And, of course, manly and warlike qualities were every bit as important in bushido as they had been in “the way of the man.” The most cherished values in bushido were courage—moral and physical—and loyalty to one’s feudal lord. Loyalty to one’s feudal lord, however, did not extend to one’s lord’s lord, i.e., the shogun. While the samurai of the Bakufu reserved all of their loyalty for the shogun, the samurai of Satsuma devoted their loyalty to the daimyo of Satsuma, the samurai of Choshu to the daimyo of Choshu, and so on. And a samurai was expected to demonstrate his loyalty through courage, even at the risk of his own life. The importance placed on courage and loyalty served a vital purpose: the preservation of order in feudal society. The samurai placed more importance on the welfare of their feudal lord than that of even their own families. Things changed, however, during the final years of Tokugawa rule, when many of the samurai began to devote their loyalty (and lives) to the Emperor. This, of course, led to the restoration of Imperial rule, which, in turn, brought about the end of feudalism and samurai society altogether—and with it, the demise of bushido.