The best writers of Japanese history are, quite naturally, Japanese. Nearly all of them concentrate on the most important era in modern Japanese history: the final fifteen years of the Tokugawa Shogunate, from the arrival of Perry in the summer of 1853, which kicked off the revolution, to the fall of the Tokugawa Shogunate in late 1868. Japanese writers call this era “Bakumatsu,” literally “end of the shogunate.” I describe it as “the samurai revolution at the dawn of modern Japan.”

Japanese writers concentrate on the Bakumatsu not only because it is the beginning of modern Japan, but also because it is by far the most interesting and spellbinding era in Japanese history. In writing about this history they naturally focus on the most powerful and spellbinding personalities of the era. These include such household names as Sakamoto Ryoma, Saigo Takamori, Katsu Kaishu, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, Takasugi Shinsaku, Yoshida Shoin, Katsura Kogoro, Takechi Hanpeita, Nakaoka Shintaro, Okubo Toshimichi, Sakuma Shozan, Yamanouchi Yodo, Tokugawa Nariaki, and last but not least the Shinsengumi, an organization whose leaders, Kondo Isami and Hijikata Toshizo garner the most attention. Readers of my books are familiar with all of these personalities and more.

When I started studying this history over thirty years ago, I was living in Tokyo. At first I read everything I could get my hands on about the Bakumatsu. It didn’t take long before I discovered that there was a gaping dearth of material in English about the Bakumatsu. So I naturally focused on Japanese writers, and after a few years of reading I was able to discern the best among them. I adopted their approach to writing this history, including their focus on the most powerful and spellbinding personalities. These Japanese writers have been my teachers throughout my writing career. My debt to them is enormous.

Following is the first part of a series of articles in which I introduce these writers. (In keeping with normal Japanese practice, their names are presented with family name first.)

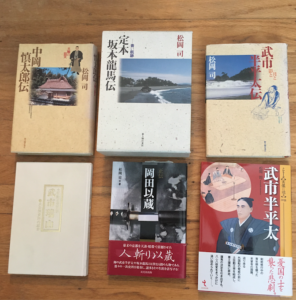

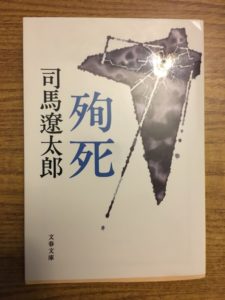

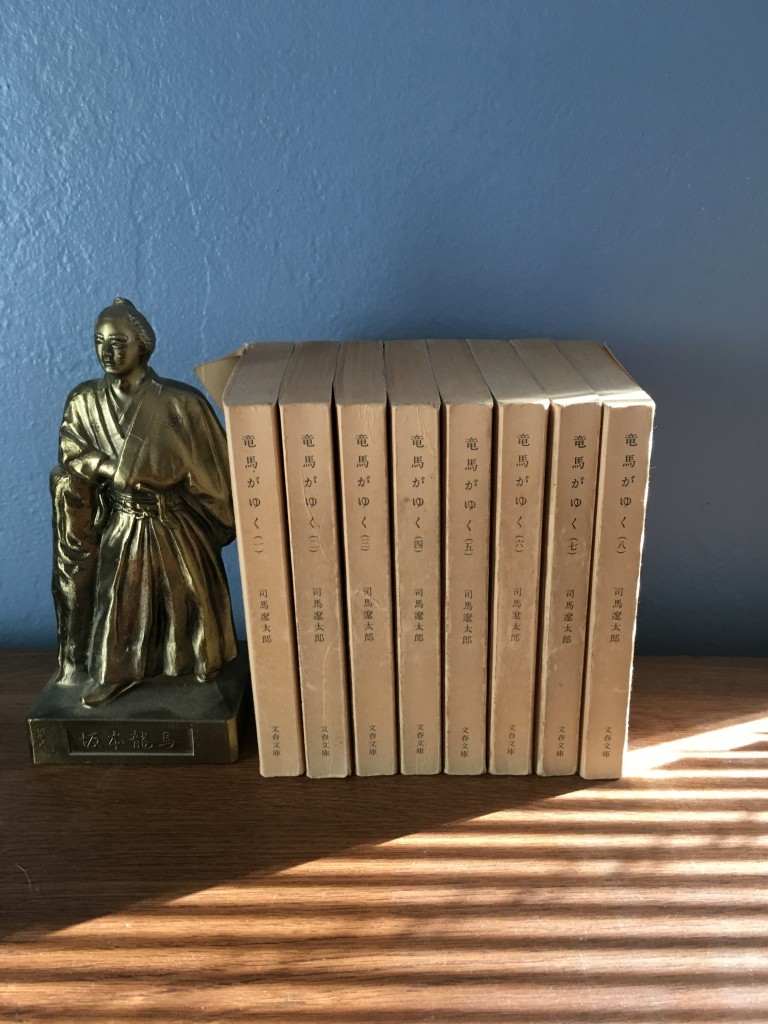

Hirao Michio (平尾道雄) (1900 – 1979) : Hirao Michio might be called the “godfather” of Tosa historians during the 20th century. His biographies of Sakamoto Ryoma, Nakaoka Shintaro, and Yamanouchi Yodo are definitive. His two most well-known books on Ryoma are probably Sakamoto Ryoma: Kainetai Shimatsuki (坂本龍馬 海援隊始末記) and Ryoma no Subete (龍馬のすべて). Of his writings on Nakaoka, I have mostly referred to Nakaoka Shintaro: Rikuentai Shimatsuki (中岡新太郎 陸援隊始末記). (The “Kaientai” in the title the first Ryoma biography cited refers to Ryoma’s Naval Auxiliary Corps in Nagasaki. The “Rikuentai” in the title of the Nakaoka biography refers to Nakaoka’s Land Auxiliary Corps in Kyoto.) Hirao’s history of the Shinsengumi, Teihon Shinsengumi Shiroku (定本新撰組史録 = The Definitive History of the Shinsengumi), was published in 1928, shortly after Shimozawa Kan’s more famous Shinsengumi Shimatsuki (新選組始末記). Like Hirao’s other books, it is invaluable. I referred to it while writing Shinsengumi: The Shogun’s Last Samurai Corps. I have also referred to Hirao’s Ishin Ansatsu Hiroku (維新暗殺秘録), a collection of accounts of historically significant assassinations during the Bakumatsu.

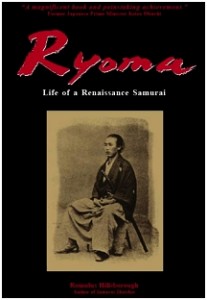

The closest I ever got to actually meeting Hirao Michio was vicariously through Ogura Katsumi, then-curator of The Sakamoto Ryoma Memorial Museum in Kochi. Mr. Ogura, a former newscaster at a TV station in Kochi, served as the moderator of a symposium about Sakamoto Ryoma held in Yonago City, Tottori, in May 2002. I was invited as a panelist and stayed at the same hotel as Mr. Ogura, who briefly shared with me memories of Mr. Hirao and also of Marius Jansen, the Princeton historian perhaps best known for his biography Sakamoto Ryoma and the Meiji Restoration. I regret that I never had the chance to meet Prof. Jansen, whom Mr. Ogura had met in Kochi. While the two of us spoke at our hotel, Mr. Ogura told me that my “Japanese pronunciation is better” than Prof. Jansen’s – mere flattery, I’m sure! Mr. Ogura’s books include Ryoma ga Nagai Tegami wo Kaku Toki (龍馬が長い手紙を書く時 = When Ryoma Wrote Long Letters). Mr. Ogura passed away in May 2005.

For updates about new content, connect with me on Facebook.