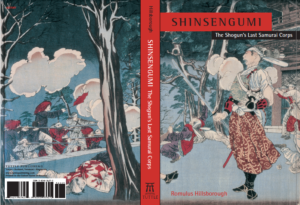

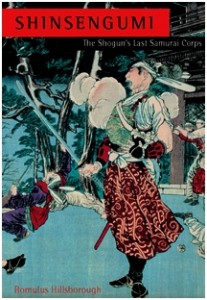

The cover of my book Shinsengumi: The Shogun’s Last Samurai Corps depicts corps commander, Kondo Isami, at the desperate Battle of Katsunuma against Imperial forces the month before the shogun’s castle at Edo would be surrendered to the Imperial government. Below is an excerpt from my book without footnotes. (Just prior to this the Shinsengumi had been renamed Koyochinbutai (“Pacification Corps”)).

On March 4, [1868] . . . they marched through a heavy snowstorm. On the following day, as they reached the summit of Sasago Pass, the most forbidding point along the road, word arrived that Kofu Castle had fallen to some three thousand imperial forces led by Itagaki Taisuké of Tosa. Had Kondo’s corps arrived one day earlier, the castle might have been theirs for the taking.

Kondo attempted to boost his troops’ morale by lying to them that six hundred reinforcements from Aizu would arrive the next morning. Hijikata rushed back to Edo to get reinforcements from among the hatamoto [samurai in service of the shogun]. Meanwhile, Kondo led his corps westward across the snowy mountainous terrain. Numerous corpsmen, despairing of victory, deserted. They reached the town of Katsunuma, five miles east of Kofu, on the same day, March 5. Only 121 corpsmen remained. In the mountains they erected a makeshift fortification, where they positioned their two cannon. In the town they constructed a barrier. In the mountains and the roadway they lit fires to intimidate the enemy, and waited for Hijikata’s return.

Far from being intimidated, some 1,200 enemy troops attacked at noon the following day.

Having been trained in modern warfare, they had the clear advantage over Kondo’s corps – both in sheer number and superiority in arms. Kondo’s men, meanwhile, particularly those who had been in Kyoto, enjoyed the advantage of experience in battle, but not in the use of artillery. Amid the smoke from the nearby fires, the Pacification Corps attempted to defend with their two cannon. There was not a man among them, however, with expertise in firing these large guns. In their inexperience, they misfired. As the enemy pounded them with heavy artillery fire, they had to resort to their rifles. The enemy closed in and charged with drawn swords. Sato Hikogoro’s peasant militia, consisting of twenty-one men, fought fiercely against the charge, as did the warriors of the Pacification Corps. Kondo’s men could not see for the smoke in their eyes. After two hours of fighting they had no alternative but to scatter into the surrounding mountains, and eventually retreat to Edo in defeat. In the Battle at Katsunuma, the Pacification Corps suffered eight dead and more than thirty wounded. Only one of the enemy was killed, and twelve wounded. [end excerpt]

Some readers have wondered about the original artwork on the book cover. Below are some details, from the websites of the National Diet Library and 西南戦争錦絵美術館 (Seinansenso Nishikie Bijutsukan), an art museum themed on the Satsuma Rebellion. (The painting is used on the book cover courtesy of Masataka Kojima, curator of the Kojima Museum.)

Title: 勝沼駅近藤勇驍勇之図 (Katsunuma-eki Kondo Isami Gyoyu no Zu)

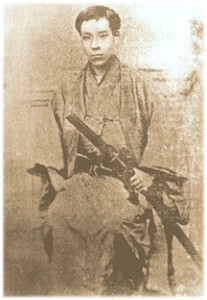

Artist: 月岡芳年 (Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1839-1892; photo below)