Recently I’ve been posting a lot of material about Sakamoto Ryoma. One of Ryoma’’s closest cohorts in the revolution to topple the Tokugawa Bakufu was Takasugi Shinsaku, the leader of Choshu’s revolutionary army. Aside from a bout of the smallpox that nearly killed him at age nine, Takasugi reportedly spent a relatively uneventful childhood as the only son of a high-ranking samurai in Hagi, the castle town of Choshu. Not much is known about his childhood, although a few anecdotes have been passed down.

One day during the New Year holiday of his fifth year, as he flew a kite near his home in observance of a New Year tradition, a visitor appeared. The visitor, a samurai, was dressed formally for the occasion in fine clothes–hakama and haori displaying his family crest–a gift from the Choshu daimyo. He had come to exchange New Year’s greetings with the Takasugi family. Just as he passed by the boy, the kite fell to the ground near a muddy patch of melting snow. The visitor accidentally stepped on the kite, crushing it. Since nobody was present but a small boy, he disregarded the incident and continued toward the house. But the boy was angry and picked up a handful of mud, with which he threatened to soil the visitor’s clothes unless he apologized. The visitor begged the small boy’s pardon and continued on his way.

Another episode indicative of Takasugi Shinsaku’s indomitable spirit involves the custom among the samurai of Hagi to send their young sons to the local execution grounds to witness the beheadings of criminals—which was supposed to nurture bravery. One day his mother prepared a boxed lunch and told him to go and watch the beheadings with other samurai boys. After the first beheading some of the boys ran home in horror. But not Shinsaku, who ate his boxed lunch and remained until the end of the day to watch the entire series of executions.

(source: Furukawa, Kaoru. Takasugi Shinsaku. Osaka: Sogensha, 1986; pp. 14-16)

For updates about new content, connect with me on Facebook.

Read more about Takasugi Shinsaku in my historical narrative, Samurai Revolution, and my biographical novel, Ryoma: Life of a Renaissance Samurai.

Ryoma: Life of a Renaissance Samurai, the only biographical novel about Sakamoto Ryoma in English, is available on Amazon.com.

“[He] had a cool head, and a certain power about him that was hard to penetrate. He was a good man.” (なんとなく冒しがたい威権があって、よい男だったよ。) (Katsu Kaishu about Sakamoto Ryoma)

Sakamoto Ryoma & Katsu Kaishu

In Part 4 of this series (Nov. 24, 2015), I quoted Sakamoto Ryoma’s assessment of Katsu Kaishu as “the greatest man in Japan.” The respect between the two men was clearly mutual. During the months after the two had first met, Kaishu mentioned Ryoma numerous times in his journal, including in an entry dated Bunkyu 3/5/16 (16th day of the Fifth Month of the Japanese year corresponding to 1863), when Kaishu, then-vice commissioner of the shogun’s navy, wrote that he would send Ryoma to Fukui to solicit financial support for the private school in Kobe which Kaishu was about to establish for the sake of Ryoma and other renegade samurai (ronin) who had enlisted to study under him. In all of these journal entries Kaishu refers to Ryoma, who was twelve years younger than him, as “Ryoma-shi.” The character for “shi” (子), which when pronounced “ko” means “child,” is in this sense used as an honorary and indicates that Kaishu perceived in Ryoma an element of greatness or at least extraordinary ability, as Matsuura Rei explains in his biography of Katsu Kaishu. And in the future, three decades after Ryoma’s death, Kaishu had nothing but praise for him. In an interview with the Yomiuri Shinbun, a national newspaper, given on April 3, 1896, Kaishu said that Ryoma “had a cool head, and a certain power about him that was hard to penetrate. He was a good man.”

Read more about the indispensible relationship between Kaishu and Ryoma in my historical narrative, Samurai Revolution and my biographical novel, Ryoma: Life of a Renaissance Samurai.

For updates about new content, connect with me on Facebook.

Ryoma: Life of a Renaissance Samurai, the only biographical novel about Sakamoto Ryoma in English, is available on Amazon.com.

After the assassination of the shogun’s regent, Ii Naosuke, in the Third Month of the Japanese year corresponding to 1860, the revolution was led by samurai of Satsuma, Choshu, and Tosa. Around this time in Tosa emerged two men who would inform the revolution—both charismatic swordsmen originally from the lower rungs of Tosa society.

Takechi Hanpeita was a planner of assassinations and stoic adherent of Imperial Loyalism and bushido, whose political agenda led to his downfall and eventual death. Sakamoto Ryoma, one of the most farsighted men of his time, had the guts to throw off the old and embrace the new as few men ever have—and for his courage, both moral and physical, he was assassinated on the eve of a revolution of his own design. And while Hanpeita and Ryoma were close friends, they had contrasting personalities, as indicated in the following anecdote taken from my Samurai Tales:

[begin excerpt] Known for their ability to consume vast amounts of sake at a single sitting, the young men of Tosa were wont to drink a potent local brew as a condiment to political discourse. One day, upon leaving a political meeting at Hanpeita’s home, Ryoma, as was his habit, relieved himself in his friend’s front garden, so that after he had left the stench of stale urine remained. When Hanpeita’s wife complained about Ryoma’s “sickening habit,” he turned to her and sternly said, “Ryoma is a man of consequence to the nation. I think you can tolerate that much from him.” [end excerpt]

[The above portrait of Takechi Hanpeita is on exhibit at the Sakamoto Ryoma Memorial Museum in Kochi. The statue of Ryoma is at Katsurahama in Kochi.]

Read more about the lives of both men in Samurai Tales and my historical novel, Ryoma: Life of a Renaissance Samurai.

For updates about new content, connect with me on Facebook.

Ryoma: Life of a Renaissance Samurai, the only biographical novel about Sakamoto Ryoma in English, is available on Amazon.com.

今にてハ日本第一の人物勝憐太郎殿という人にでしになり (“I have now become the disciple of Katsu Rintaro, the greatest man in Japan”)

The outlaw Sakamoto Ryoma first met Katsu Kaishu, a high-ranking officer of the shogun’s nascent navy, at the latter’s home in Edo, some time during the final few months of the Japanese year corresponding to 1862. During the following spring, while Kaishu moved forward with plans to establish an official Naval Training Center at Kobe, Ryoma, as Kaishu’s right-hand man, recruited his friends from Tosa and elsewhere, most of them renegade samurai (i.e., ronin) like himself, to study under Kaishu. Following is a slightly edited excerpt from my historical novel, Ryoma: Life of a Renaissance Samurai:

[begin excerpt] While Kaishu used his close relationship with the seventeen-year-old shogun, Tokugawa Iemochi, to gain permission to establish an official Naval Training Center in Kobe, Ryoma used his influence among the Imperial Loyalists in Kyoto to recruit nearly one hundred of them for Kaishu’s private school. The Bakufu’s [i.e., shogunate’s] institution and the private academy would share the costly facilities supplied by the Edo government. Under Kaishu, Ryoma, at age twenty-eight, was on the verge of realizing his dream of establishing a navy. He drolly expressed his excitement in a letter to his sister, Otome:

“Well, well! In the first place, life sure is strange. There are some men who are so unlucky that they die by breaking their balls just trying to climb out of a bathtub. Compared to that I’m extremely lucky: here I was on the verge of death but I didn’t die. Even if I tried to die I couldn’t, because there are too many things which compel me to live. I have now become the disciple of Katsu Rintaro, the greatest man in Japan, and I am spending every day on things I have always dreamed about. I don’t intend to return home until I’m around forty.” [“Rintaro” was Katsu Kaishu’s given name, “Kaishu” being his pseudonym.]

Part 3 of this series was posted on November 23, 2015.

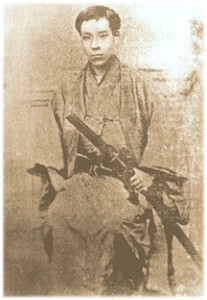

[The above photo is from Sakamoto Ryoma Zenshu, Miyaji Saichiro, ed. Katsu Kaishu is in the middle, with Ryoma on the right.]

For updates about new content, connect with me on Facebook.

Ryoma: Life of a Renaissance Samurai, the only biographical novel about Sakamoto Ryoma in English, is available on Amazon.com.