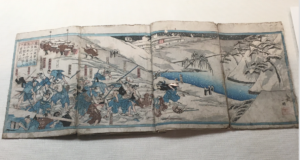

Ii Naosuké, regent to the shōgun, was the archenemy of Tokugawa Nariaki, daimyo of Mito. As regent, he was the most powerful man in Japan. He was assassinated in broad daylight at the gate called Sakurada-mon, a main entrance to Edo Castle, on an unseasonably snowy morning in spring 1860, by seventeen Mito samurai and one from Satsuma. The murder was the most brazen offense ever committed against the Tokugawa Bakufu and the most politically significant assassination in an era plagued with assassination and bloodshed. The Bakufu collapsed around eight years later. Following is an excerpt from Samurai Revolution (without footnotes):

The regent’s sedan was surrounded by more than sixty men of [Ii Naosuké’s] Hikoné Han, including bodyguards, foot soldiers, luggage bearers, and sandal carriers. The Hikoné men wore wide-brimmed sedge or lacquered hats and cloaks of oiled paper. Since the hilts of their swords were covered with small cloth pouches to protect against the falling snow they could not readily draw their blades. Suddenly one of the assassins threw off his hat, removed his jacket, drew his sword and cut one of Ii Naosuké’s guards across the forehead, then slashed another man diagonally across the body. One of the assassins fired a pistol, at which signal several others drew their swords and charged. “Look out!” one of the Hikoné men shouted, as the regent issued an order for his guards to remain by his side. But in the chaos all but one of them became separated from the regent, brandishing their swords and spears against the sudden attack. Several of the assailants managed to penetrate the guards’ line and reach the sedan. They stabbed the regent through the side of the vehicle and pulled him to the snowy ground. The one Satsuma man, Arimura Jizaémon, beheaded him, and holding the head up high triumphantly announced that he had killed Ii Naosuké. [end excerpt]

I wrote in detail about the political rivalry between Ii Naosuké and Tokugawa Nariaki in Samurai Revolution. Part I of Samurai Assassins, entitled “The Assassination of Ii Naosuké and the Beginning of the End of the Tokugawa Bakufu,” provides a detailed account of the so-called “Incident Outside Sakurada-mon.”