My Inspiration In Writing About the Samurai Revolution (Part II)

Recently I mentioned my inspiration in writing about the Samurai Revolution. The samurai I write about “kick ass,” I said. But I did not say that I am sure that all of them were capable of seppuku– self-disembowelment. This is unthinkable to most people in the 21st century. Following is my rendition of an eyewitness account of the seppuku of Takéchi Hanpeita of Tosa, included in my Samurai Assassins:

Kneeling between his two seconds, Takéchi inspected the blade of the dagger before replacing it on the stand in front of him. Then he removed both arms from his stiff ceremonial robe, baring his shoulders, and loosened the sash around his waist, exposing his lower abdomen. Again he took up the dagger and, wrapping the hilt with the piece of white cloth, plunged in the blade and pulled it across his belly. Blood gushed from the wound as he repeated the process two more times, cutting three horizontal lines as he had vowed. Then deliberately placing the dagger on his right side, he fell forward with both arms extended. That instant the two seconds drew their swords, stabbing him through the heart six times until he was dead. [end excerpt]

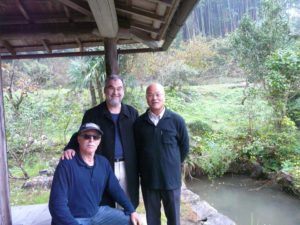

I had the opportunity to visit Takechi’s ancestral home, including his grave, in Kochi in November 2015 (below), with my friends Douglas Stiffler and Mamoru Matsuoka. Professor Stiffler is a great-great grandson of Katsu Kaishu. Mr. Matsuoka, a native of Kochi, is Takéchi’s preeminent biographer. He describes the setting of Takechi’s house as follows (my translation included in Samurai Assassins):

“[in] a quiet mountain hamlet . . . bathed in bright sunshine. Surrounded on three sides by mountains, the south side opens to a small field, and the drawing room is filled with sunlight throughout the day. To the north lies the Kōchi Plain, beyond which is a view of the Shikoku Mountain Range, with the Pacific Ocean spreading out just beyond the hills to the south. The blue sea of these southern climes, which sparkles brightly during ordinary times, can, when the weather turns bad, change to a gray raging billow, enough to frighten even a sailor—and hit Tosa hard.

Often I ask myself: Why do I spend so much of my life writing about men of a culture that is completely foreign to my own, who lived and died in the century before my birth? My answer is always the same: Because these guys are the most inspirational, awesome, and just downright likeable men I have ever “known.” Or in the vernacular, they kick ass! Among them are Katsu Kaishū, the focus of my Samurai Revolution; and Yamaoka Tesshū, Kaishū’s close friend and confidant, renowned swordsman, and Zen adept. Following is an excerpt from Samurai Revolution (without footnotes):

Yamaoka Tesshū died of stomach cancer on July 19 [1888] at age fifty-three. On the day of his death, Kaishū called on him at his home in Tōkyō. Upon entering the house he found the sword master surrounded by visitors and sitting in zazen—the practice of Zen meditation—wearing a “pure white kimono” under a Buddhist robe, “with perfect composure,” Kaishū recalled. He asked his friend if the end was near. “Tesshū opened his eyes slightly and, smiling, replied without [showing] pain, ‘Thanks so much for coming, Sensei. I am about to enter Nirvana.’ Then I said to him, ‘Become Buddha,’ and left.” According to Kaishū’s oral recollection ten years later in October 1898 (Meiji 31), Yamaoka died shortly after he left him. At the time of his death, “he had a white fan in hand.” Chanting a Buddhist prayer, he “smiled at all present, including his wife, children, and relatives,” and, even after he finally died, maintained the proper sitting posture. In manifesting Buddhist enlightenment, Kaishū remarked, Yamaoka demonstrated “just how well he understood bushidō.”

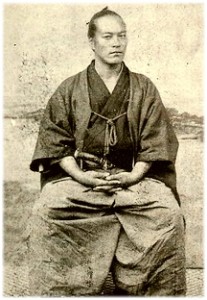

(The photograph of Yamaoka Tesshū is in Samurai Revolution, courtesy of Fukui City History Museum.)

This evening my wife mentioned that she saw an NKH program about Ernest Satow’s villa in Nikko. It reminded me of Katsu Kaishū and his relationship with Satow, secretary to Sir Harry Parkes, the British minister to Japan, around the time of the surrender of Edo Castle in 1868. I reminded my wife of the portrait of Kaishū (above), based on the photograph at the British Legation in Yokohama taken by Satow. At that time Kaishū was in command of the forces of the fallen shogun. “I was so very sleepy at the time,” Kaishū recalled years later. “But they dragged me over there. Satow took it, because, as he said, ‘You’re going to be killed.’” Both Satow and Parkes were worried for his life, Kaishū said. And so they urged him to take refuge at the British Legation. Kaishū refused their offer on the grounds that he wouldn’t have been able to perform his job, “if I feared assassination. I thought that dying for the country was the duty of any [patriot] and wasn’t about to do something as cowardly as hide out at a foreign legation.”

Katsu Kaishū is “the shogun’s last samurai” of Samurai Revolution: The Dawn of Modern Japan Seen Through the Eyes of the Shogun’s Last Samurai. I was motivated to write the book based on of my immense admiration for the man – for his moral and physical courage and his humanity.

[The photo of Ernest Satow’s summer villa, on the southern shore of Lake Chuzenji, built in 1896, is from The Japan Times, December 5, 2016.]

Meiji Restoration hero Sakamoto Ryoma is a national icon in Japan. My first encounter with Ryoma was through Shiba Ryotaro’s popular biographical novel, Ryoma ga Yuku. So fascinated was I by Ryoma’s life story, particularly his indispensible role in the “samurai revolution at the dawn of modern Japan,” that I thought that people all over the world should know about him. Which was why I wrote Ryoma: Life of a Renaissance Samurai (Ridgeback Press, 1999), the only biographical novel about Ryoma in English. “It is a cultural loss that an historical figure of such magnificent stature has failed to gain the full attention of the Western world,” I wrote in the Preface. Since then, for many years, I have hoped that, through my book, Ryoma would become a household name around the world.

I think that things are moving in that direction. But a film about Ryoma, produced and/or directed by a major Hollywood name, would “seal the deal.” Which is why for these past few years I have reached out to “Ryoma fans” around the world for their ideas to make this dream a reality. Please keep your ideas coming – through my website or my Facebook page.

Think big! Create! Persevere!