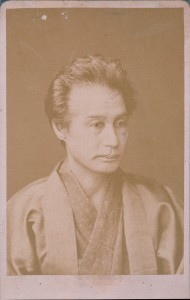

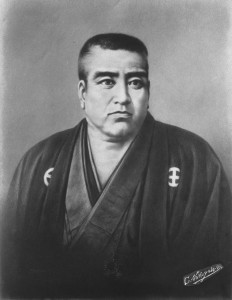

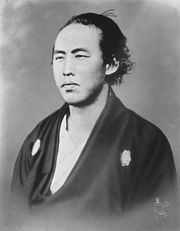

Katsu Kaishū: “the shōgun’s last samurai”

As a New England Yankee, [Edward Warren] Clark might have cherished a question posed nearly three years before the Meiji Restoration, by Abraham Lincoln, who, during the American Civil War, was beset with difficulties and woes similar to those of Katsu Kaishū’s. “Haven’t you lived long enough to know that two men may honestly differ about a question and both be right?” Lincoln asked a congressman who called for the hanging of rebel leaders shortly before Lee’s surrender to Grant. Certainly Katsu Kaishū, revered and reviled by men on both sides of Japan’s civil war, had feelings similar to Lincoln’s, when, having been “unexpectedly placed in a most responsible position,” he struggled to bring the two opposing sides together to save Japan from ruin. Clark recognized this quality in Kaishū. “It is not often that a man can see both sides at once,” Clark wrote, adding that Kaishū did—“and that is what made him a unique character.” [from Samurai Revolution]