As we Americans witness the travesty of democracy this week at the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia, the “City of Brotherly Love,” I am reminded of the philosophy of a great man of the people in nineteenth century Japan.

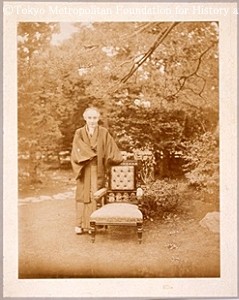

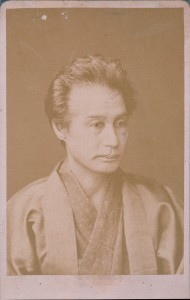

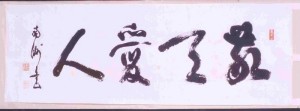

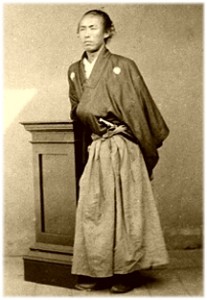

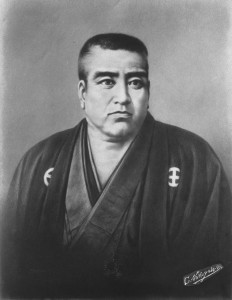

As I wrote in Samurai Revolution, Saigo Takamori, one of the great leaders in Japanese history, practiced a religious philosophy informed by his cherished maxim: “revere Heaven, love mankind,” which represents a Confucian ethic that dictates the relationship between the people, the government, and the Emperor—in a universe ruled by Heaven. . . . Heavy is the responsibility of the officials who oversee the everyday affairs of the [government]. Since they directly control the fate of the people, one blunder by just one official can mean catastrophe for a great number. As a leader of the people, a government official must win the hearts and minds of the people. To do so, he must put aside self-interest for the benefit of the people, who have no choice but to obey him. If he shows any sign of selfishness, he will incur the enmity of the people and no longer be able to lead them. Since his only function is to benefit the people, based on the “will of Heaven,” the people’s suffering must be his suffering, and the people’s pleasure must be his pleasure. . . . Saigo, who hailed from a poor lower-samurai family, had served as a clerk in the tax collector’s office. He knew first-hand of the hardships of the people.

I think that this samurai born and bred in feudal Japan had a better sense of “the people” than the so-called Democrats who, in cahoots with the Democratic National Committee, just nominated a blatantly corrupt candidate for president of the United States.

Read more about Saigo Takamori in my book Samurai Revolution.