A recurring question among Western historians and writers is the relevance of bushido, “the way of the warrior,” in Japan’s military during World War II. Bushido is often attributed to the refusal of the Japanese forces to surrender despite certain defeat and death at such battles as Iwo Jima. Military historian Geoffrey Wawro, in an interview on ww2history.com, asks: “To what extent did this Bushido Code trickle down to the ordinary troops? To what extent was it the province of officers? And the more menial troops, did they really buy into all this code of the Samurai stuff?” Professor Wawro concludes that they did, based on the occurrences at Iwo Jima and elsewhere. He cites “this whole mentality about how it was disloyal and dishonourable to surrender,” that did not exist among Western forces. (http://ww2history.com/experts/Geoffrey_Wawro/War_in_the_Pacific)

Fair enough! But I’m not sure that the valor displayed by Japanese soldiers during WWII was the stuff of bushido. To understand this, first we need to take a look at the origin of bushido, which dates back to the early period of the Tokugawa Bakufu, the military government that ruled Japan from 1603 to 1868. This is discussed in “Chapter 8: A Brief Discussion of Bushido,” of my forthcoming book, Samurai Revolution: The Dawn of Modern Japan Through the Eyes of the Shogun’s Last Samurai. Following are some slightly edited excerpts:

________________________________________________________________________

The state ideology during the Tokugawa period was Neo-Confucianism, under which society was divided into four strictly defined castes: merchant, peasant, artisan, and samurai. Samurai education was based on Neo-Confucianism and intertwined with bushido, which, in turn, was inseparable from “the way of the sword” and Zen. The samurai class dates back to the twelfth century. Bushido, however, is much younger, dating back only as far as the mid-Edo period, during the era of Genroku, a turning point in cultural history about a century after the founding of the Bakufu, when many of the warrior class lived relatively easy lives compared to their predecessors. During the peaceful Tokugawa period many samurai became administrators—which is not to say, however, that they forgot the arts of war. As professional warriors who received stipends from their feudal lords, they were expected to answer the call to arms at any time. There is an old saying: “the sword is in the man”; and it was also said that there was no such thing as a samurai without a sword. Even as the samurai took up the pen, they were required to wear the two swords; and many of them practiced the martial arts—with the sword, with the spear and on horseback.

Until the advent of bushido, the most important qualities in a samurai had been bravery, honor, and a strong masculine spirit, based on a set of values sometimes called “the way of the man.” Bravery naturally meant bravery in battle, begot of honor and strength of spirit. “The way of the man” worked just fine during the violent Warring States period preceding the Tokugawa period, when a man’s worth was measured by his valor on the field of battle. However, since “the way of the man” lacked a strong underlying moral code, it came to be frowned upon as barbaric, and even immoral, during the peaceful, orderly, and more refined Tokugawa period. The samurai required a new set of morals to replace the old. Bushido derived as a combination of Confucianism and “the way of the man”—without the barbarism of the latter—and might be best defined as “the way of the gentleman.”

The eight virtues of Confucianism—benevolence, justice, loyalty, filial piety, decorum, wisdom, trust, and respect for elders—were incorporated into bushido. Most, if not all, of these qualities were also valued in “the way of the man,” but were not the measure of a man in the older system. And, of course, manly and warlike qualities were every bit as important in bushido as they had been in “the way of the man.” The most cherished values in bushido were courage—moral and physical—and loyalty to one’s lord. And a samurai was expected to demonstrate his loyalty through courage, even at the risk of his own life. The importance placed on courage and loyalty served a vital purpose: the preservation of order in society. The samurai placed more importance on the welfare of their lord than that of even their own families. Things changed, however, during the final years of Tokugawa rule, when many of the samurai began to devote their loyalty (and lives) to the Emperor. This, of course, led to the overthrow of the Bakufu and restoration of Imperial rule, which, in turn, brought about the end of samurai society altogether—and with it, the demise of bushido.

Perhaps the most eloquent spokesman of bushido was Yamamoto Tsunetomo of the Saga clan, author of Hagakure, the classic text of samurai values: how a samurai should live, think, and die. The book is based on seven years of nightly talks by Yamamoto, starting in 1710. Yamamoto extolled the warrior spirit and austere way of life. He admonished his fellows in Saga not to indulge themselves in “the luxury of peaceful times” under the Bakufu, during which so many men had “neglected the way of arms.” He emphasized the duty of absolute loyalty and subordination to their lord. He said that for the greater benefit of their lord, each man must know his place and fulfill his duty within the feudal hierarchy of the clan, without regard to personal likes or dislikes. And indeed, each man must be ready to die at any time for the lord of Saga.

“Bushido is found in dying,” asserts the key line of the memorable first chapter. When confronted with two alternatives, living or dying, death is the only choice—and one must die immediately. Some say that dying without achieving one’s aim is a “futile death.” However, such thinking belongs to men who practice a “vain,” false bushido, and not to a true samurai. But when pressed between two alternatives one will not necessarily make the right choice. (After all, it is only human and rational to prefer life over death.) But regardless of a man’s past actions, as long as he chooses death he will not be disgraced—no matter how others might judge him afterwards. Such a man, professes Yamamoto, understands bushido. To “gain the freedom of bushido,” then, a man must be “prepared to die at any time, morning and night.” By so doing, he will be able to serve his feudal lord “throughout his entire life, without error.”

Bushido, for all its bellicosity, was also inherently humane. Kaionji Chogoro, in his acclaimed biography of Saigo Takamori, points out that during Japan’s wars with China and Russia at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, and even as late as World War I, when bushido was still very much alive among Japanese soldiers, the Japanese Army was admired around the world for its humane treatment of prisoners of war. This implies that by World War II the Japanese military had lost the humanity of bushido.

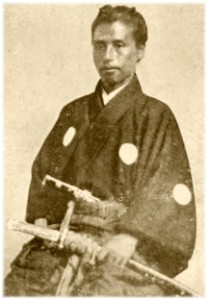

Katsu Kaishu, San Francisco, 1860: used in “Samurai Revolution” courtesy of Ishiguro Keisho

Katsu Kaishu, “the shogun’s last samurai” of my Samurai Revolution, had the following to say about bushido in the 1890s, long after the demise of the samurai class:“The samurai spirit must in time disappear. Although it’s certainly unfortunate, it doesn’t surprise me at all. I have long known that this would happen with the end of feudalism. But even now, if I were extremely wealthy, I’m sure that I’d be able to restore that spirit within four of five years. The reason for this is simple. During the feudal era the samurai had neither to till the fields nor sell things. They had the farmers and the merchants do that work for them, while they received stipends from their feudal lords. They could idle away their time from morning until evening without having to worry about not having enough to eat. And so all they had to do . . . was to read books and make a fuss about such things as loyalty and honor. So, when feudalism ended and the samurai lost their stipends, it was only natural for the samurai spirit to gradually wither away. If now they were given money and allowed to take things easy like in the old days, I’m sure that bushido could be restored.”

For updates about new content, connect with me on Facebook.